You know how it is, you’re having a perfectly normal conversation with somebody you think you know, and suddenly they say, ‘That’s just not like me, I’m a Capricorn’, and you’re thinking, ‘I hadn’t realised you were as daft as a brush’…

The great thing about owls is they aren’t like that — millions of years of evolution have honed them into ultra-efficient killing machines and none will make a judgement based on your star signs. Probably what they’re thinking when looking at you is, ‘I’m sure that thing’s too big to eat; but I’ll keep watching in case it’s dangerous?’

All that owls need to do is catch and kill prey on a regular basis; find a mate, then a suitable place to nest and rear offspring successfully; and for all of these things natural selection has adapted them well… otherwise they’d be extinct. Survival doesn’t require cleverness in the way that we think of it; no owl will be entering a pub quiz any time soon, because that’s not what ‘wise owls’ do.

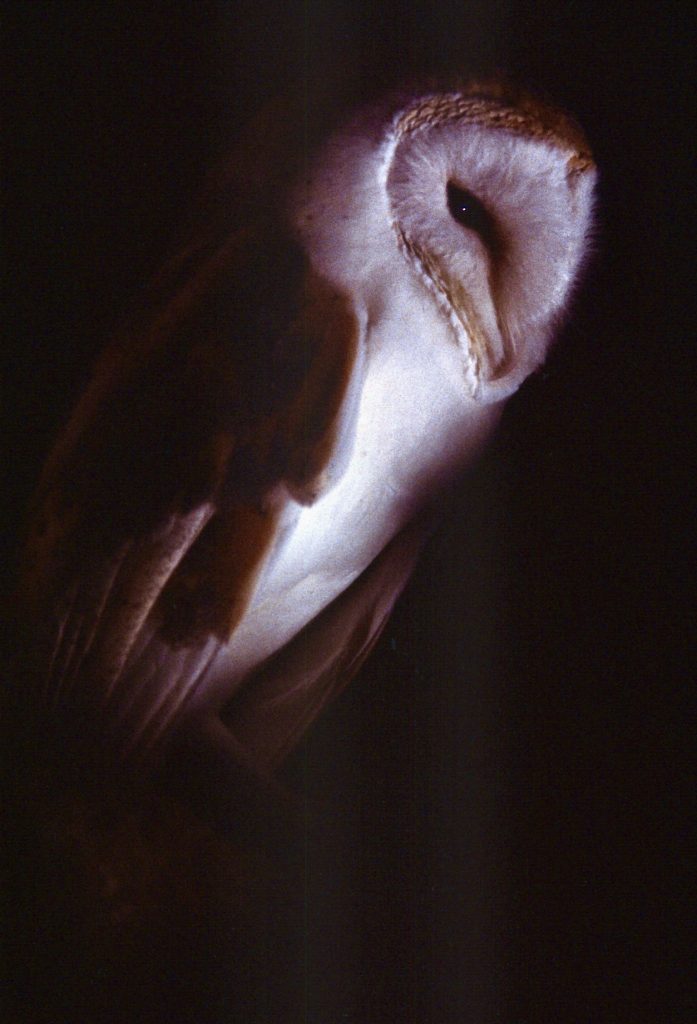

Here’s ‘a wise owl’. Certainly this one’s fairly cute for a killing machine, but clever?…That’s a different story.

The impression we have is that owls are thoughtful, because unlike most birds they have flat faces and as predators need to judge distance using binocular vision; consequently, their eyes are located at the front of their heads, and these organs of vision are usually so big and adorable they are a super stimulus for our brains and this encourages us to like them. Add to this, beaks that look a bit like noses and suddenly we’re thinking, these creatures look a bit like us, so they must think like us… but that’s really stretching it.

Various animals seem to grab our attention — mostly mammals; but frogs, toads, parrots, owls and even snails have their fans. Owl enthusiasts will surround themselves with imagery relating to their favourite subject — pictures on the wall, place mats on the table and cuddly toys in the bedroom.

For the love of owls...

I don’t see myself as a rabid owl enthusiast and yet after a head count I’ve noticed quite a few dotted around the house. Rooted somewhere deep in our psyche these unusual looking bird are just waiting to come to mind, but over the years my relationship with them has been mostly practical: every now and again I’ve been required to film one, and suddenly they’re part of making a living.

The first owl I filmed for television was for a documentary on the wildlife of churchyards — it was a barn owl… or to be precise, it was three barn owls, and they taught me something… These are beautiful birds but have a habit of making their surroundings surprisingly dirty for all their hauntingly pristine whiteness. Clearly, the magic hold that owls have over our minds turns almost everything that they do into a positive.

Owls push out waste material from both ends, which you really start to notice when you spend long hours working with them. Most creatures excrete from their rear ends, but owls also regularly throw up pellets — waste materials of digestion that attract flies and other small creatures to feed and lay eggs upon these macabre little parcels.

During the spring of the project I was suddenly looking after three young captive barn owls, converting my Victorian outhouse into a film set, and constructing a window from which they would hopefully emerge as if from a church tower.

In reality churches haven’t had owls or even bats in their belfries for a very long time, because those responsible for maintaining the interiors of churches prefer to avoid accumulating bat poo, bird droppings and owl pellets.

For years now, the chances of finding owls spending their days hiding away in church towers has been reduced to almost zero, as most windows have been meshed to prevent birds from entering.

However, if owls had still been living a church going lifestyle, the only other option would have been to build a scaffold next to a church tower from which I need to film a single shot, and that wasn’t very cost effective. Back in the 1980s, it was easier for me to build a church window set and film captive owls coming and going, even if in reality they’d be unlikely to do so.

Wildlife film-makers rarely admit to deception, but we all have to own up to the realities of what is possible in a world that is rapidly disappearing. I don’t think it matters one hoot whether an owl exits a real window, or a fake one, because nothing about the bird’s behaviour changes. Nobody questions an edit in a natural history film, because if an audience wanted to experience natural events in real-time they’d be waiting for days. However, as soon as you tighten up the progress of events the result is a story; and the real problem with telling a story is the disappointment of the viewer should they discover the deception.

So, there I was… faking it; building a facade on the front of my outhouse and using the outdoor toilet next to it as a hide to film from, essentially by knocking a small hole in the wall. On the outside of the set window was an outdoor enclosure into which the owls could emerge, but they never did. Even sitting in the window would have been helpful; and if flying was beyond them, just hopping out of frame would have been enough, but they wouldn’t do any of these things. It was a complete waste of time, and I ended up feeding the birds inside the little room they’d adopted as their home, a home that I never managed to persuade them to leave.

The outhouse was next to the kitchen, and the flies coming to visit the mess the bird’s created was disagreeable. The owls weren’t equipped to fly any distance; and after a couple of months I returned them to the person who had reared them in preparation for release into the wild. I am aware that most owl enthusiasts would be singing the praises of experiencing such wonderful birds first hand, but I couldn’t wait to see the back of them. They whole thing had been a time consuming failure. I’d been unintentionally mislead about what these owls would do, and was a long way past the point where I was going to train them to fly through my phoney window. They were the wrong birds for the job and never again did I make such an expensive mistake.

Soon after my year of filming in graveyards, I moved onto another film project for the BBC in the backwoods of Maine where I would meet a great horned owl destined to become one of the most famous owls in natural history writing. I returned to Maine on several occasions over the course of the next year and a half, spending much of my time high on a wooded hill at the camp of scientist and writer Professor Bernd Heinrich. The thing about Bernd is that he is not only an exceptional naturalists but one of the most impressive zoologists of his generation. He’d rescued a fledgling great horned owl from the snow and the bird was always somewhere close to his cabin, either sitting on a log, or in a tree close by. He had been named Bubo: if you can name a hobbit Bilbo, then why not an owl Bubo, after all it is latin for his Genus — the New World horned owls and Old World eagle owls make up the genus Bubo.

Eventually, after many hours of observation, Bernd wrote ‘One Man’s Owl‘ which like most of his books became a classic of natural history writing. The bird was semi-wild, and would come to Bernd without much trouble; better than that, he would fly to food in a manner that was entirely predictable. One day Bernd dangled something dead and unpleasant just behind my head and young Bubo came swooping in to take it, providing a shot I could never have achieved in the wild. We repeated this several times, the owl on each occasion dropping from it’s perch just a little way off and then gliding towards the lens, dipping low enough to appear as if he might be about to crash into me, but rising at the last moment to a position just above my head — each time I felt claws brushing through my hair, but they didn’t close until locked onto the free lunch that I couldn’t exactly feel behind my head, but could faintly smell. When a bird of prey’s talons touch prey, they usually snap closed as a reflex action and my hair got pulled, but it was nothing personal. If an owl really flies at you with intent… then you certainly know about it.

A great horned owl has a pounds per square inch (psi) grip of around 300 — 500, whereas most humans manage a grip of just a few pounds per square inch.

A few years later I found myself in the high mountain woodlands of New Mexico filming the small nocturnal flammulated owl. It was a surprise when the scientist working with the birds told me he could chainsaw out the back of the tree they were nesting in and they would remain entirely undisturbed. If you needed to observe or weight young birds this was perhaps an effective way of doing it, but I was sceptical. Chainsawing a tree before the owls started nesting seemed a better option, but how many trees would you need to cut into to guarantee a nest being present later in the year? Predicting such events is very hit and miss.

The section removed from the back of the nest could be taken out when filming, then set back and wired into place very quickly. There are probably a dozen good reasons why this wouldn’t be done today, one of which is that flammulated owls are now endangered in some areas of their range. For the most part this has been down to habitat loss. After being set up by the bird biologist, I filmed the owls both during the day and at night using artificial light — but standing at the top of a ladder tied almost perpendicular to what remained of an old conifer miles from anywhere, in otherwise total darkness, was rather spooky.

The filming occurred more than 35 years ago when a great many species were far less threatened than they are today; but even back then if I hadn’t been confident about what I was doing, I wouldn’t have been filming; and in this case, certainly not without the supervision of a scientific advisor who had been working closely with the birds. I haven’t named him because many will consider this kind of intrusiveness unacceptable; but as none of his birds ever seemed disturbed and the information gleaned went into conserving the species, I didn’t have a problem with it. Nevertheless, I am not sure we need to see every wild bird on the nest just for a television programme, although there is no doubt that this kind of media exposure is the best way to get a general audience informed and proactive in conservation… But don’t try this at home… you might lose an eye! The alternative is to film captive birds on sets and there are many people who are equally disturbed by this alternative dishonesty.

Using artificial light attracted more moths that I have ever seen at any one time outside of the tropics. The owls were easy going, but there was always the potential danger that an adult bird arriving back at the nest might get spooked and launch into my face. Owls have inflicted serious damage to people who have worked this closely with them in the wild, causing facial damage and even the loss of an eye.

I was filming less than a foot from the bird, and couldn’t believe how tolerant the flammulated owls were, although I only worked with birds for very short periods, never more than 20 minutes a night before leaving them to get on with their lives. The success of the project was mostly in the planning; followed by working quickly without any sudden movements that might disturb them. I used a variety of techniques to minimise disturbance: a light source that could be turned up rather than one that could only be turned on, and dark gloves to prevent sudden glare from my hands. Simple things but very effective.

Unless a hide has been set up and birds are entirely unaware of your presence, the 20 minute rule is a good one. I’ve worked in this way with several bat species including vampire bats at their roost as well as variety of nesting birds, but you can’t do this with every species.

Some birds are not troubled by this kind of exposure, but many will be, unless you have almost unlimited time to get them used to a new experience; most importantly you can’t just try it out to see, and that is why such filming endeavours work best if they are associated with a research project that has already clearly defined the ground rules.

It would be impossible to list every owl I’ve filmed or photographed because there have been so many — some have been captive, but most have been truly wild.

I have in the past been fairly mean when using film stock and there are many occasions when I didn’t wind on far enough before taking pictures, resulting in a light leak that affected the first frame of the roll. For some reason when I photographed owls this happened rather a lot, but I often quite liked the results. I could claim that these were artful pictures, but I won’t go that far — although the random nature of what turned out was often quite interesting.

‘Tawny in Red’ was a resident at the Hawk Conservancy Trust at Weyhill, Hampshire and it was an extraordinary bird. This owl would fly to wherever was required and land to order; and rather usefully could fly slowly alongside a moving vehicle so that it might be easily tracked by a camera. Straight away I must admit that owls are capable of remarkable things, but in fairness this birds super abilities were to some degree down to handler and Trust Founder Ashley Smith, but there was no doubt in my mind that this was a very special bird.

This wild burrowing owl was photographed on open grassland, and had the habit of standing tall, stretching itself up to gain a little extra height when it was trying to make out anything that was moving, often at some distance. This was accompanied by complicated head movements, giving the bird a comic demeanour. The behaviour however was strictly functional, allowing the bird to judge distance. The owl would react this way when anything new came into view: this might be an old bag blowing in the wind, a coyote, or just a human who hadn’t yet noticed the owl was there — in the reverse situation the observations were seldom as acute: people just don’t notice as much as an owl does; certainly any owl that takes the trouble to monitor its surroundings is more likely to survive than one that doesn’t.

Everybody has favourites, but more often than not, mine are functional. Burrowing owls are high on my list because they are active during the day which gives a film-maker at least a chance. In the mid 1980s I worked with these delightful birds on a site in New Mexico and became quite enamoured by their behaviour.

They would sit outside of their burrows during the day, or on top of a dead tree stump or power line pole, but unlike most owls, were more inclined to present more interesting daytime behaviour. Many species remain at rest during daylight hours, giving you little more to film than a rotating head and the occasional blink; but burrowing owls are different — they are generally more dynamic, even if sometimes this involves little more than moving in and out of their burrows. Movement is essential to a television audience’s experience; and usefully the most dramatic activity these owls would perform was to dive-bomb walkers and joggers; joggers being the preferential targets, perhaps because they were moving faster and considered more of a threat.

Several years after filming the flammulated owls, I took a road trip with my wife Jen across Route 66 and made a slight detour to re-visit my old favourites. Unlike so many animals I have returned to see, the owls had not been swamped by development or disturbance. They were living their lives pretty much the way they had been on my previous visit when I’d had the luxury of being paid to be in their presence and could give them far more time.

Good telephoto lenses are expensive, and increasingly photographers are getting far too close to wildlife trying to get a better shot, and they are often doing so using mobile phones. As a group, photographers are becoming a nuisance and it’s way past the time when we need to be thinking about our priorities, because no matter how hard we try, somebody will always have a better picture of the animals we are trying to photograph than we are ever going to get on the inappropriate cameras and lenses many of us are using. Clearly it’s time for all of us to ease off a bit and give what remains of the natural world a bit more space.

When working with animals I’ve always attempt two styles of photography. The first and most essential is to record events at a specific moment in time: it is rewarding to take a great picture but on occasions this isn’t the point. The second kind of picture is taken with a view to getting an attractive image, usually playing with framing and exposure to create a mood, and this isn’t as difficult as it sounds, and most of us can manage it with a bit of practice. However, now and again something special comes together — an animal is in the right place at the right time and suddenly the lighting comes good and you grab the moment, which is about as authentic as it gets for a photographer.

I presently live in a Canadian suburb, which isn’t the best place to take pictures of wildlife, but even developed areas have something to offer, especially if you can find a bit of woodland that hasn’t been felled somewhere between all of that housing. In my case, ‘a river runs through it’ with natural woodland on either side: this is a byway for many animal species, and there is no telling what might show up. Recently a beaver took up residence and started chewing down small trees. Now and again I see a barred owl that likes to sit in a particular stand of trees. My son walks a different route and he sees a different owl. Yesterday his owl was sat in its usual place, but on this occasion it was being mobbed from above by a heron. The owl on my walk seldom has anything that interesting going on, but a couple of years ago the owl was sitting unusually low in a tree close to the path. The sun was going down and I could see the light would come good in just a few minutes and all I needed to do was photograph it, but I wasn’t carrying a long lens. The question was, could I jog home, pick one up and get back in time? It took fifteen minutes to turn that around, and when I got back the owl was still there, and suddenly looking at me wondering what all the fuss was about.

The sun was casting its rays through the branches and there was very little life left in them, but there was enough. The owl bobbed her head at me, trying to work out what I was doing. I imagined she was thinking, ‘What are you up to you fool?’… but that’s just the’ psych bending power of the owl’ driving me to put human thoughts into her skull. She soon lost interest and turned her head to one side and I took my picture. My preference was to think that she’d worked it all out — the meaning of life and all that goes with it, but that of course was preposterous. Everything that was clever about this owl was inside my head. But never mind that — there before me was the most extraordinary creature… and that should have been enough, because this was as good as it was ever going to get.

In memory of my father — Elliott Keith Bolwell. 22/8/22 – 22/1/21.

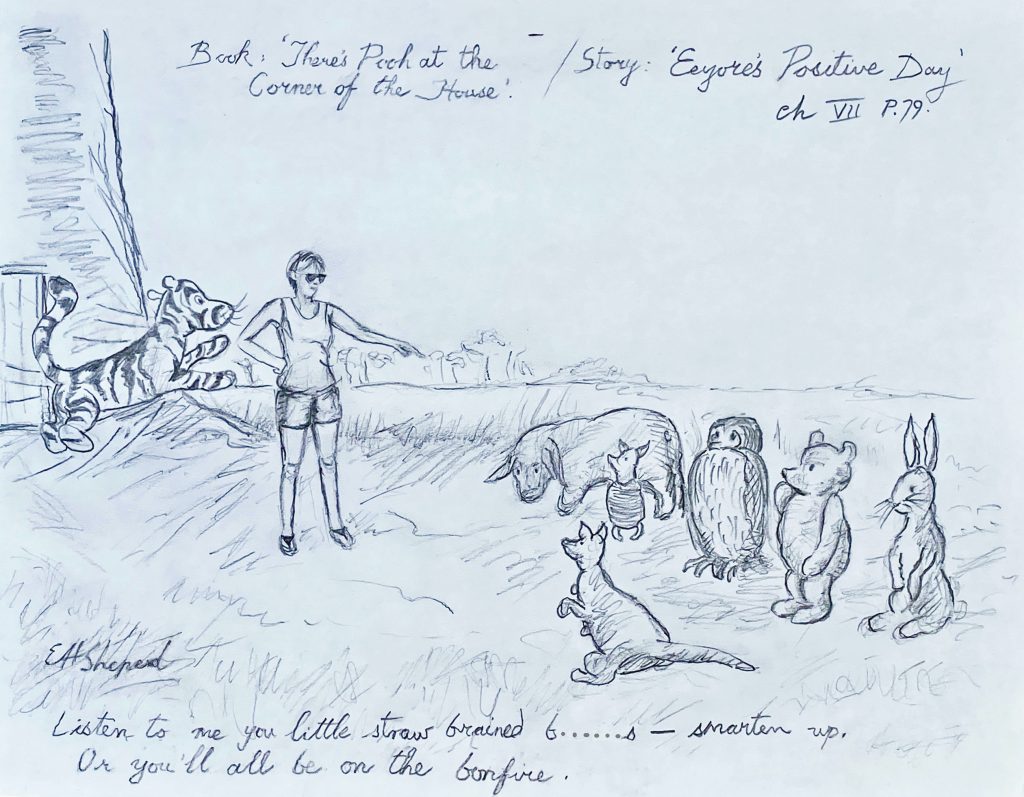

Nigel posted the pic you used of John’s owl. John checked out your blog and he was most amused to see his early artistic attempt on show.

I don’t think he ever got any better at wildlife portraits but is a professional beer drinker now and a mean guy at the barbecue!

We have regular visits from tawny owls in our back garden and occasionally see a barn owl quartering the fields an the farm.

Lots of memories of filming in the churchyard in the new forest using my rabbits as extras and John still has the framed photo of himself you took that used to have pride of place on mum and dads hall wall

Regards

Mike

Thanks Mike. I thought John might have that picture of him in the churchyard with the cine camera. Unfortunately the tawny owl picture wasn’t registering when he looked at the article — I’ve now sorted it.

Injured wild tawny owls often seem to recognise when they are being helped and cooperate with rescuers. Barn owls, on the other hand, are very sweet if they have been captive bred, but I can t convince myself that I have ever met a bright one. An owl expert once told me that, were you to see the head of an owl devoid of its feathers, you would find nearly all eyes and very little skull or brain. Not long after, the person running an owl display at the Royal Armouries museum in Leeds, UK, talked about the abilities of the massive European eagle owl. He said it was difficult to teach it a routine more complex than fly to the back of the crowd, fly back for a snack .

Thank you for your comment, I thought it very interesting.