From Gambling to God.

For reasons that seem inexplicable there’s no shortage of stupidity…

It’s everywhere… In politics, in the pub, even on street corners – out there at this very moment there will be somebody carrying a placard that says, ‘The end of the world in nigh’… a person a bit like me perhaps, although my preference is to garner at least a little scientific evidence before making a startling claim.

There’s a man who stands at a road junction close to where I live, and he carries a sign that says, ‘Jesus Comes Soon’. I’ve been wanting to tell him that his wording could be better, but sadly the lights always change before I can get his attention. Incorrect use of language is not necessarily a sign of stupidity, but spending most of your waking hours at a road junction with a message from God is a whole other thing.

Stupid is as Stupid Does.

We all do daft things and for that reason alone we should be judged by our actions rather than our I.Qs. Social media perhaps demonstrates how to reward stupidity best. Clearly, gathering ‘likes’ from ‘like’ minded people reinforces beliefs in ill-considered opinions; and it works so well because almost the entire world is available on line.

Even those who aspire to wallow down amongst the stupidest people on the planet can attract an appreciative audience. All that is required is an opinion, the ability to type into a computer…and then press enter. In an instant a nonsensical view is made available to a huge number of ‘like’ minded individuals… and that’s not such a good thing. Technology is there for us to make use of, and it isn’t technology’s fault that we find ourselves so frequently sinking to the depths rather than rising to a challenge.

Nevertheless, for the more intelligent members of society who are operating above the lowest common denominator, it is still possible to get caught out when believing without evidence. Predicting the chances that something might happen is now fairly well understood, but many of us can still be fooled by the icing on the cake – all the sugary stuff that we just can’t resist absorbing.

Amongst the commonest of these beliefs is that we can somehow beat the odds using nothing more than our own good fortune at times when we just feel lucky. Gambling can be both thrilling and addictive, but when the odds are running against us, longterm outcomes can be disappointing and sometimes life changing.

Some argue that most accidents are avoidable,

especially for the brightest amongst us who think ahead and prepare accordingly; certainly insurance companies understand the odds of ‘getting things right’, because insurance depends for its success on predicting who will and who will not ‘get lucky’ – this because our genetic make ups and behaviours skew our lives towards certain outcomes which can be analysed mathematically. Most accidents are no longer regarded as random, even when the results are down to external forces. Closer to home a lot may now be predicted by looking at the genes we carry, this just another tool for measuring when the odds are running against us.

With a rise in political correctness it has become increasingly difficult to ask questions about who is really being stupid and why; and sometimes when you get on the wrong side of the word it really does get personal. As I child I was told not to discuss religion or politics and the reason given was simple – ‘it upsets people’, but at an early age I wondered if this really mattered: when people are thinking and doing irrational things it makes sense to ask the question – why?

God is right up there when it comes to asking questions and upsetting people. Those who hear voices in their heads or receive information from entities that can’t be demonstrated to exist are often thought to be suffering from mental illness, but sometimes not so much when they think God is speaking directly to them. It is difficult to understand why being religious gives you a free pass when it comes to irrational behaviour, which it must be said, cannot always be correlated directly with a person’s intelligence. Whether God exists or not is a controversial subject for some, but not liking the answers is never a good enough reason not to asking the questions.

Influencing young minds sets beliefs systems for life – lying to children is the ultimate obscenity:

I must admit to having had an odd childhood. There were no small children living in my neighbourhood and consequently I had no regular contact with people of my own age until I went to school at the age of five. My mother did have a friend who would visit our house on Tuesday afternoons with her daughter and this was no doubt regarded as a social opportunity for us children, but all that I remember about the girl, is that without provocation, she hit me very hard over the head with an enamel bowl. It was an inauspicious introduction to other children and my first experience of being attacked by another human being.

My best friend was and old neighbour – his name was Mr Tidridge and he had no children of his own which was unfortunate because he would have made somebody a great parent or grandfather. I called him Uncle Tid and spent most of my daytime hours in his presence – he was a man of infinite patience and taught me many things. We would spent most of our time in the garden and I was probably four years old when this picture was taken, as I busily moved what I thought were logs, in my wheel barrow.

One day it came onto rain heavily and I remember we were standing in the doorway of an old shed when Uncle Tid said, ‘Water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink’, and I was curious to know what this meant, which led him to give me a very basic outline of ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. Technically, his reference was off the mark, because ‘not a drop to drink’ refers to the presence of salt water. However, this mismatch between story telling and reality was harmless enough and there was no sense of indoctrination, it was simply the provision of knowledge through story telling.

One day it came onto rain heavily and I remember we were standing in the doorway of an old shed when Uncle Tid said, ‘Water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink’, and I was curious to know what this meant, which led him to give me a very basic outline of ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. Technically, his reference was off the mark, because ‘not a drop to drink’ refers to the presence of salt water. However, this mismatch between story telling and reality was harmless enough and there was no sense of indoctrination, it was simply the provision of knowledge through story telling.

As far as I was concerned time with Uncle Tid was better spent than with children of my own age, but I’d failed to understand that being with other children was just another part of developing normal social behaviour; and when the time came I was ill prepared for the next step – going to school and meeting people of my own age.

This was for me a very different world from the one I was used to and with no previous meaningful contact with other children it was a difficult experience. To me, these little people all seemed so loud and rough, and the thing I remember above all else was that they somehow managed to make the plasticine smell of poo. I really wanted to get out of my new situation at any cost and cried every morning I was re-introduced to this new and disgusting world because there was no escape.

The small preparatory private school I attended was set up in an old Victorian property. It was a dark dismal house of horrors that still had most of its original decor and it smelt of dog – I had apparently gone back to another era; but this didn’t bother me that much because the house had one saving grace – it was full of old books and the second one that I read, quite by accident, turned out to be ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’ by Lewis Carroll, and at I at once found myself in a far more logical world than the one I was being forced to live in: the madness contained within its covers appeared to me to make perfect sense… I just loved it.

In the 1951 animated Disney version of Alice, Disney got the colour of Alice’s dress wrong, and I made a point of doing the same in my illustration, which was painted many years ago: the original John Tenniel colour illustrations of the dress were made in corn yellow. Blue might simply have been a better colour for movie illustration, but judging from the fact that Lewis Carroll’s name was mis-spelt in the front credits of the film there might be other reasons entirely. I mention these details because they are good examples of the things we often confuse with stupidity, namely ignorance and indifference and neither sit very well amongst the logical thinking of A. L. Dodgson.

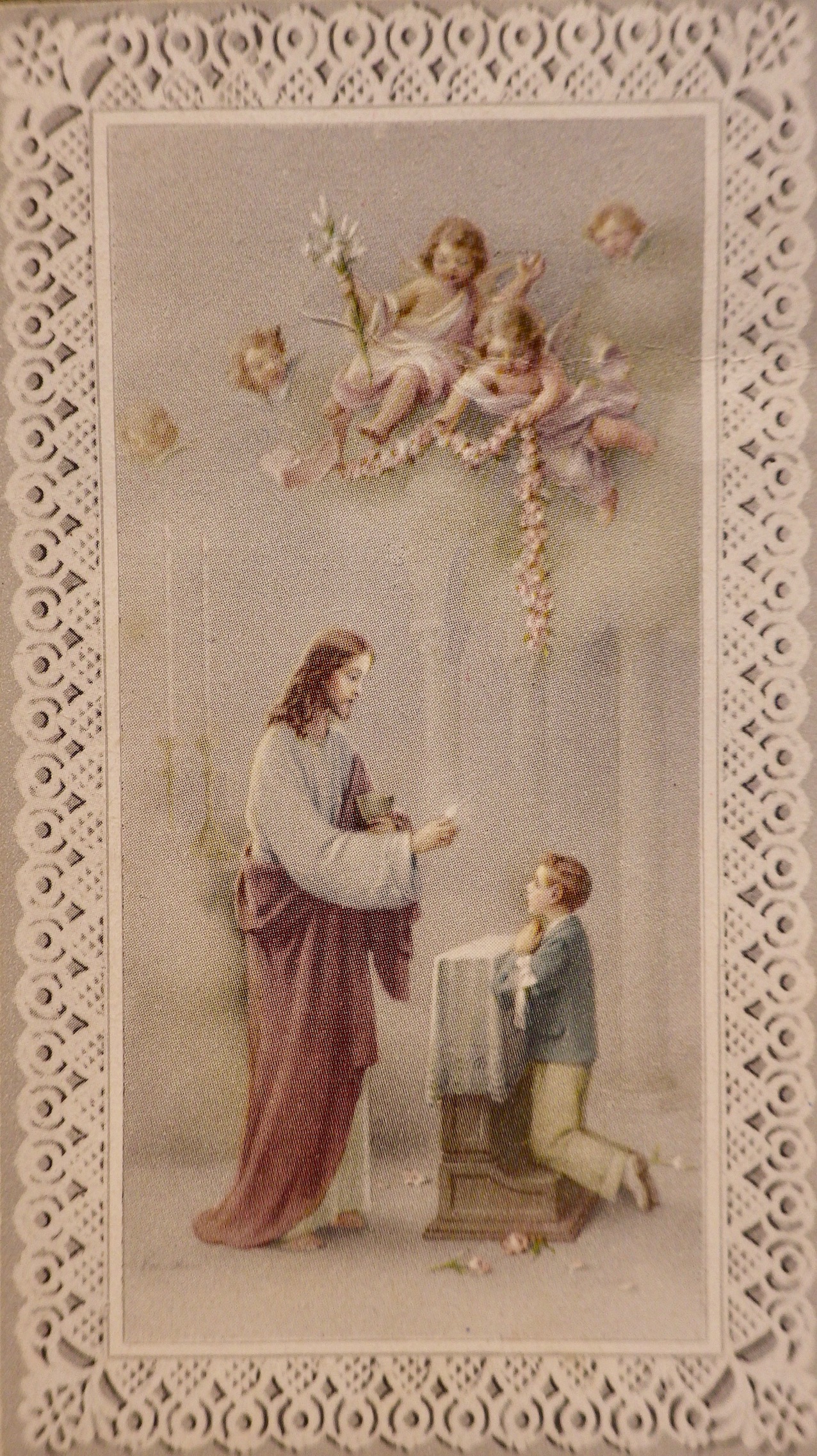

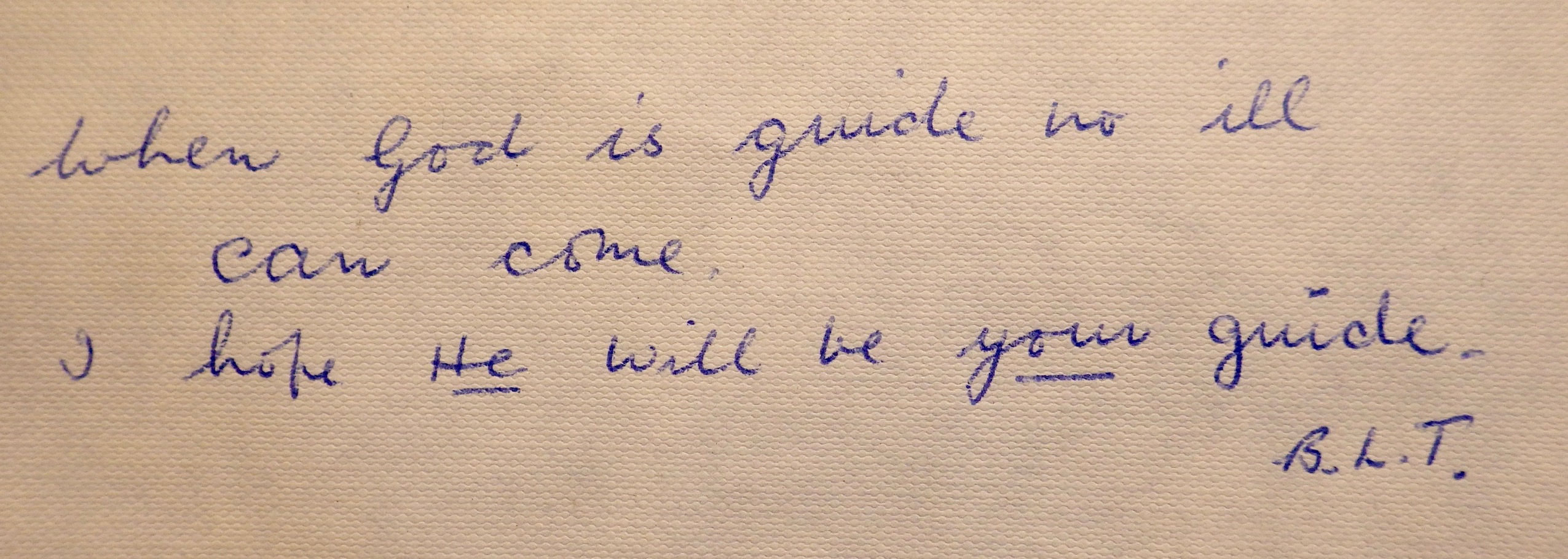

When I was forced to climb out from the organised madness of the rabbit hole, I returned to a more uncertain world, inhabited by a head mistress who was very religious; apart from her mother, she was the only teacher in the little school that she ran; and for some reason she was determined above all else, that I should be gifted a Bible – which unlike ‘Alice’ was a book I seldom opened; in particular the pictures representing the holy land were both insipid and unlikely – and to me everything about my bible seemed disagreeable – I just hated it, as I did the religious music, the Christmas carols and the prayers that went along with it. My life had been sabotaged by nonsense. Then, one day I was taken to a church service and saw adults that prior to this event I’d considered rational, but now here they were on their knees, heads bowed, mumbling in the direction of a carving of an almost naked man nailed to a cross. This was for me a genuinely shocking event and a real eye opener. It seemed that adults were just as unreliable as the children around me – they just hid it better. So much that was going on didn’t ring true… and I didn’t like it one bit. I was only seven years old, but the prevailing circumstances caused me to question everything I was learning, which must have been exasperating for any adult that came into contact with me. No adult was ever unkind during this time and in retrospect this seems remarkable because I must have been a precocious child, and my own experience of children of this sort has been that they are invariably awful. I was very polite and enjoyed education and for these reason alone I think I was favoured. Certainly I hid my mistrust of some adults judgement when it came to religion, and could see no reason to believe in anything that wasn’t demonstrably true. However, I didn’t make a big deal over things that clearly upset them: every morning I went along with saying the Lord’s prayer – with just one question on my mind – why didn’t they think this was twaddle?

As I got older I decided I would test everything that I was told by working things through from first principles, but this wasn’t so easy, and I soon realised that I didn’t have the maths skills to do the job properly which made the uncertainty of not knowing for sure frustrating. Very soon after I discovered science, and the great advantage of science was that all the things I thought I needed to know had been tested and I was soon hooked on this more than useful way of dealing with information.

Twenty-five years later I returned to visit my first school teacher and asked her directly if she was still a follower Jesus, and to my surprise she said that she wasn’t – she had stopped believing in Christianity some time previously and was now following the teachings of a Native American chief. I thought she was bats and wondered whether she was going to apologise for trying to fill my head, at a very impressionable age, with religious beliefs that she had since rejected, but it had clearly never occurred to her that the indoctrination of small children with information that she no longer believed had been an appalling act. To my mind her lack of rational thought on the subject was clear stupidity, although I appreciate for some, this is a matter of opinion… But. is it really? I mean come on! We can’t continue to think the way people used to think in the 12th Century by following unsubstantiated views that have remained unchanged for hundreds of years.

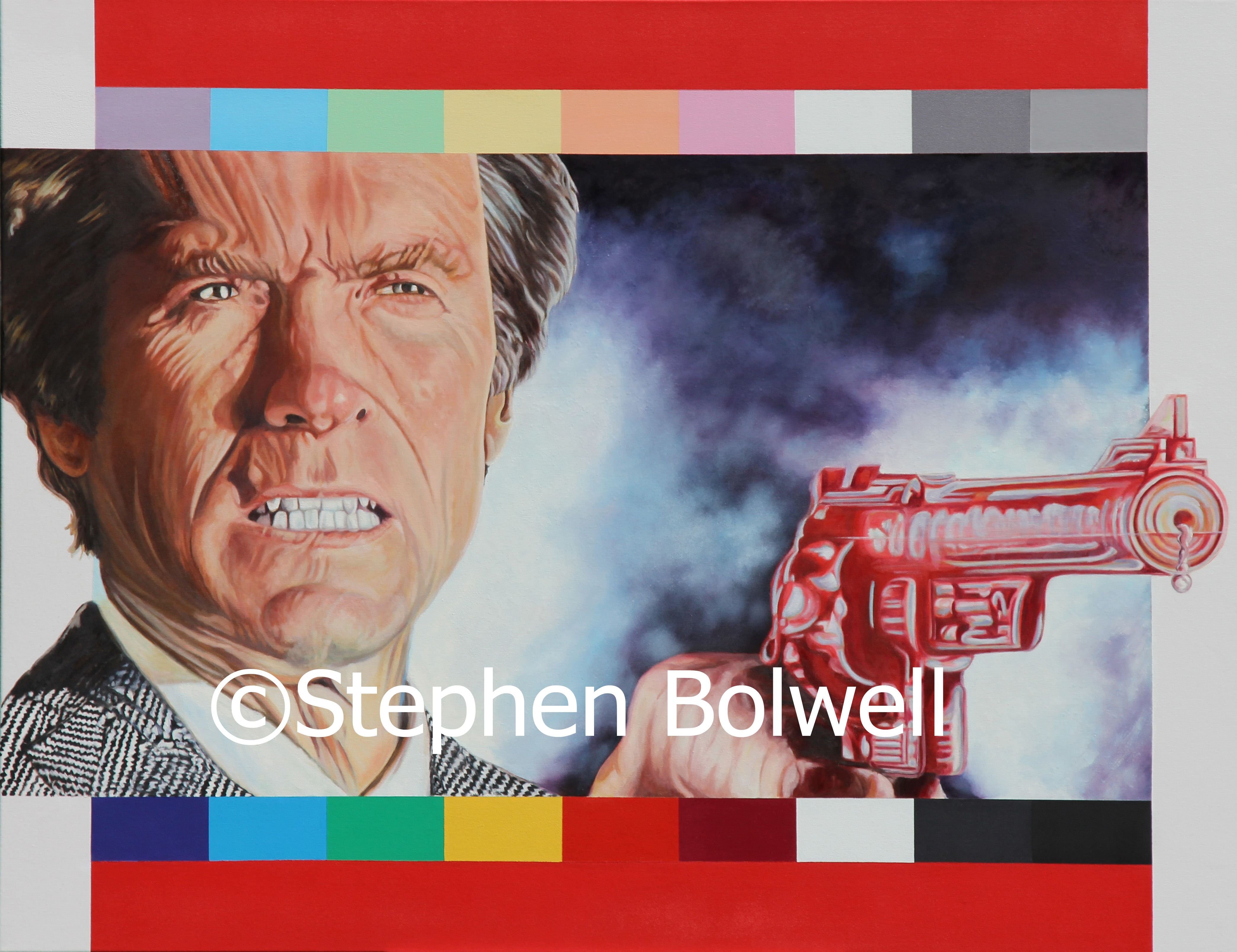

I don’t think it unreasonable to ask why so many people follow horoscopes that cannot be accurately predicted; or gamble in casinos that make no secret that the odds are stacked against their punters; and certainly it seems entirely reasonable to question why so many millions worldwide, pray to different versions of gods that rational thinkers might consider unlikely to exist. Clearly, there is a lot going on in our heads and it might be that faith, or certain types of believing without question, are genetically selected for, because belief itself provides us with some selective advantage. Believing in a certain way without question might indeed be making some of us feel more comfortable, but believing without evidence does not make things true and in many cases might be regarded as the most dangerous form of stupidity. When leaders claim their right to engage in conflict because ‘God is on their side’, we know there will be trouble; and when they think they’ve got evidence for ‘weapon of mass destruction’ without really checking, having God on your side gets them over the line. So often, the apparently harmless act of just believing can turn us into dangerously defective individuals.

Throughout many parts of Europe religious belief has been in decline for quite some time and the situation is also true for the United States although this to a lesser degree. The real question might be, not in asking what people really believe, but rather, how their belief is actually measured. Is it that religious people are becoming less inclined towards belief, or is it that people who were not religious in the first place are feeling more comfortable about admitting it?

In England during the middle ages, people were heavily penalised for not attending church, and might incur a heavy fine, but there was also the possibility of a physical punishment and in some cases death. Throughout Europe people were executed for their non-religious views, and it wasn’t so much down to ‘the not believing’, but more the consideration that they might be in league with the devil, a situation that seems almost too ridiculous to take seriously.

In Tudor times it was not uncommon to be fined for non-attendance at a church and it proved wise not to attract attention to yourself by openly questioning God because doing so could be life threatening. However, it does seem odd that with today’s level of education and understanding churches still have a place. The Roman Catholic Church has been largely discredited by repeated scandals, but when the Pope makes a statement his views still make the news, which suggests that despite a groundswell of unsavoury scandals Catholicism remains relevant to many of its followers.

There’s a lot of stuff going on that our brains are susceptible to and religious belief is high on the list.

Nobody can be sure there isn’t a god, but certainly there is no empirical evidence to support the idea that there is a benevolent one and any god that is looking out for an appreciative footballer giving thanks for having scored a goal whilst ignoring starving children somewhere else in the World, would seem to be no god at all. However, Dr Dean Hammer has claimed a God gene exits and labelled it VMAT2, and those who carry it are said to be more likely to believe in a greater spiritual force; the validity of this one off experiment has been disputed, but at least it opens up the possibility of further research into whether genes play a role in what we believe and how they operate. Certainly if there is a selective advantage to faith systems it makes sense to look for the mechanisms.

On the whole our brains like stories that make us feel more comfortable – having faith provides the opportunity to just believe which is far easier than formulating rational opinions. The term atheist is used to label those who don’t believe in God, but a belief in deities is a broad subject and a single word cannot cover all the bases.

If we are looking for truth, it should not be a question of believing or not believing, but rather asking why thinking rationally should need to be labelled. How in any case is it possible to claim that one supernatural God is more likely to exist than another. The very idea that a benevolent god exists seems so unlikely it is surprising how many people find it necessary to argue that god is an illusion, but then again there are book deals, movie projects and comedy routines that indicate there is money to be made in disputing god’s existence.

If we are looking for truth, it should not be a question of believing or not believing, but rather asking why thinking rationally should need to be labelled. How in any case is it possible to claim that one supernatural God is more likely to exist than another. The very idea that a benevolent god exists seems so unlikely it is surprising how many people find it necessary to argue that god is an illusion, but then again there are book deals, movie projects and comedy routines that indicate there is money to be made in disputing god’s existence.

Perhaps the important thing is not so much to consider the existence or non-existence of god, but rather, how the imaginary way that some people see a deity’s role in their lives affects the rest of us.

Some religious groups suggest that our dominion over the natural world is ‘all part of God’s plan’, while others claim that as we are the superior life form on the Planet, our manipulation of other species is innate, but should we follow either of these beliefs our behaviours will increasingly threaten natural environments and other life forms on the Planet. To see ourselves as above and not part of a natural system inevitably throws our continued existence into question.

With or without God, our present relationship with the natural world indicates that it is necessary for us to make changes, but we continue to dither rather than behave proactively. In the face of imminent environmental disasters we do nothing because some of them haven’t quite happened yet… and we prefer to ‘hope’ that they won’t rather than ‘accept’ that most likely they will; which might be considered the ultimate demonstration of mass stupidity. The trick it seems is to pin down the essentials and then act upon them, but our minds appear to have evolved in a way that make this difficult to achieve. For some reason we prefer to try and fix things once they have gone wrong, rather than prevent them from happening in the first place.

Increasingly, thinking – stupidly or not – is becoming a political act, and unless science can provide a precise analysis of every situation that we face – unfavourable or not – it will be very difficult to overcome the surge of erroneous ideas that many use to support unsubstantiated beliefs. Scientific evidence is being increasingly challenged by nonsensical arguments, put forward by those gambling our futures on faith and anecdotal stories; they are attempting to impress and bewilder the ignorant amongst us by simply cherry picking what best supports their poorly thought out arguments, whilst re-engineering all of the most important questions to support the answers that their audience most wants to hear. Propagating nonsense is not necessarily a demonstration of stupidity, but if the rest of us are prepared to accept such views without recourse to the facts, then clearly it is.

Around the World, large numbers of people do not appear able to move forward with rational thought based upon the evidence available because their decisions are often emotionally based. The question is, with education and reliable information so freely available, why are there so many people trying to think their way through life using faith based systems rather than thinking rationally?

Unfortunately, the use of logic does not appear to be gaining traction at a time when essential changes in our behaviours seem essential: and the sad truth is that we may not be capable of thinking clearly enough to react appropriately to the environmental problems that we now face.

We can’t say for certain that a God didn’t create the Universe or the laws that govern its existence, but just because we don’t presently know all of the answers doesn’t mean that we should automatically jump to conclusions based on mythologies; and in any case a god working on this level would make no practical difference to our everyday lives. The possibility, that God is an interventionist and pervasive in daily outcomes also seems unlikely and not supported by any of the laws of science. The most likely possibility is that believing in sudden good fortune and divine intervention are simply illusions created by our minds, and there is a certain irony in that beliefs beneficial to our species in the past, may now prove detrimental to future success.

We can’t say for certain that a God didn’t create the Universe or the laws that govern its existence, but just because we don’t presently know all of the answers doesn’t mean that we should automatically jump to conclusions based on mythologies; and in any case a god working on this level would make no practical difference to our everyday lives. The possibility, that God is an interventionist and pervasive in daily outcomes also seems unlikely and not supported by any of the laws of science. The most likely possibility is that believing in sudden good fortune and divine intervention are simply illusions created by our minds, and there is a certain irony in that beliefs beneficial to our species in the past, may now prove detrimental to future success.

It might just be that the time has arrived to put magic and mystery on the back seat and allow critical thinking, based on scientific evidence, to drive us forward. For those who haven’t noticed, science has been doing this for a century or more, but increasingly we have chosen to ignore the less palatable truths that scientific discoveries have thrown up. I doubt that Jesus is coming any time soon, but major changes are on the way, and some of them might not be good; meanwhile the clock is ticking, with many of us still set on stupid time. The question is, can we learn to think more rationally, or are we stuck with what we’ve got?