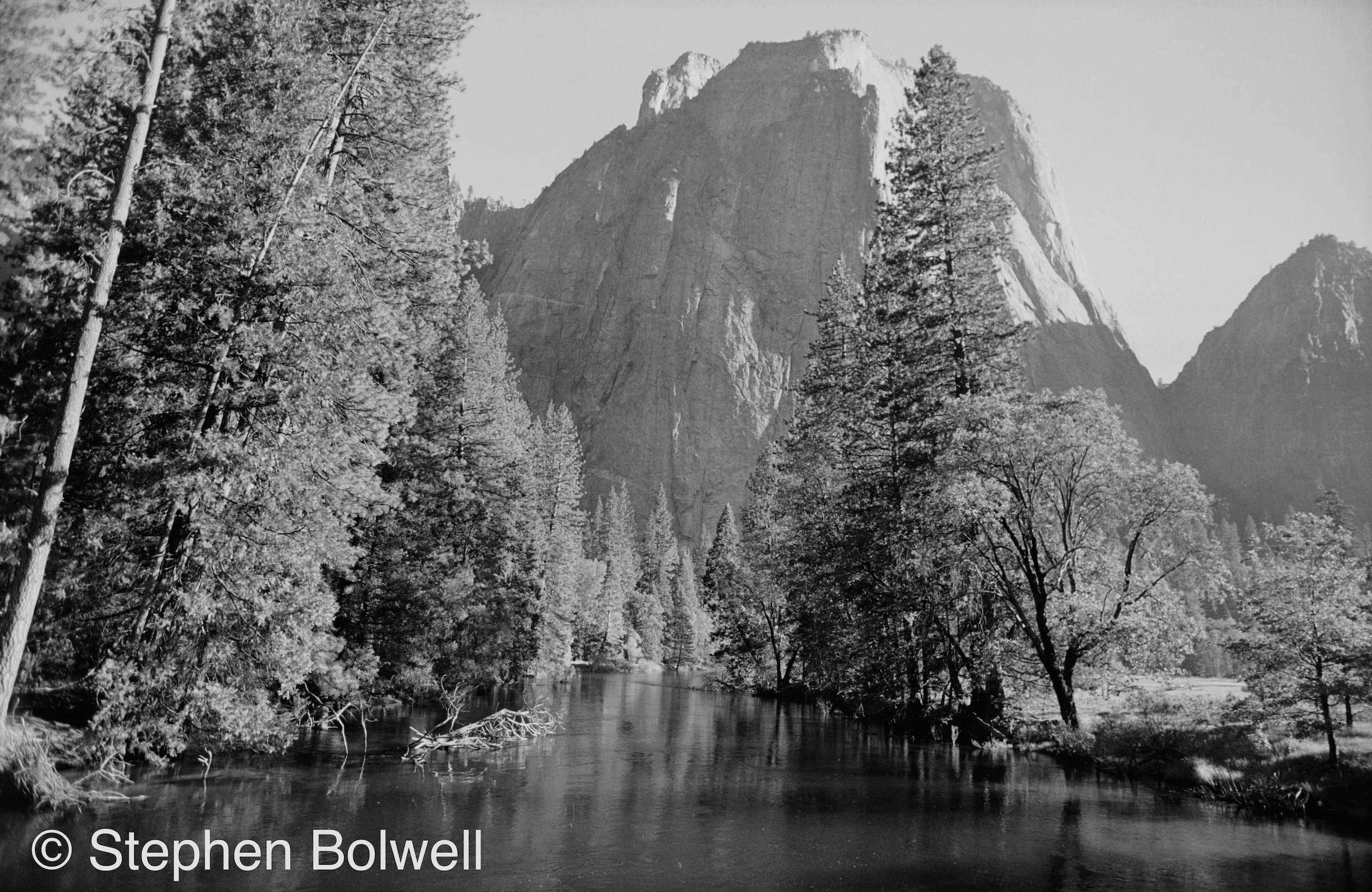

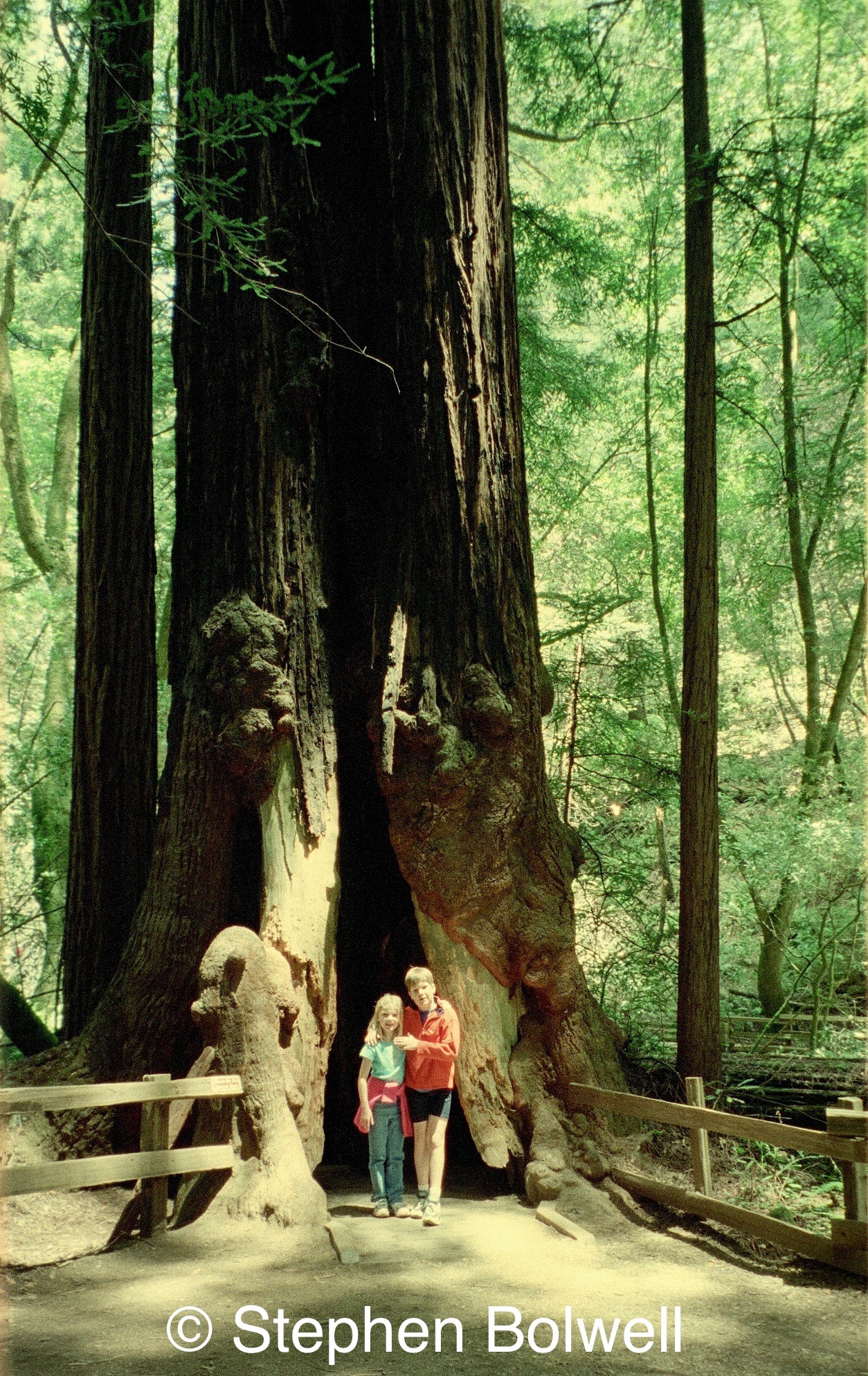

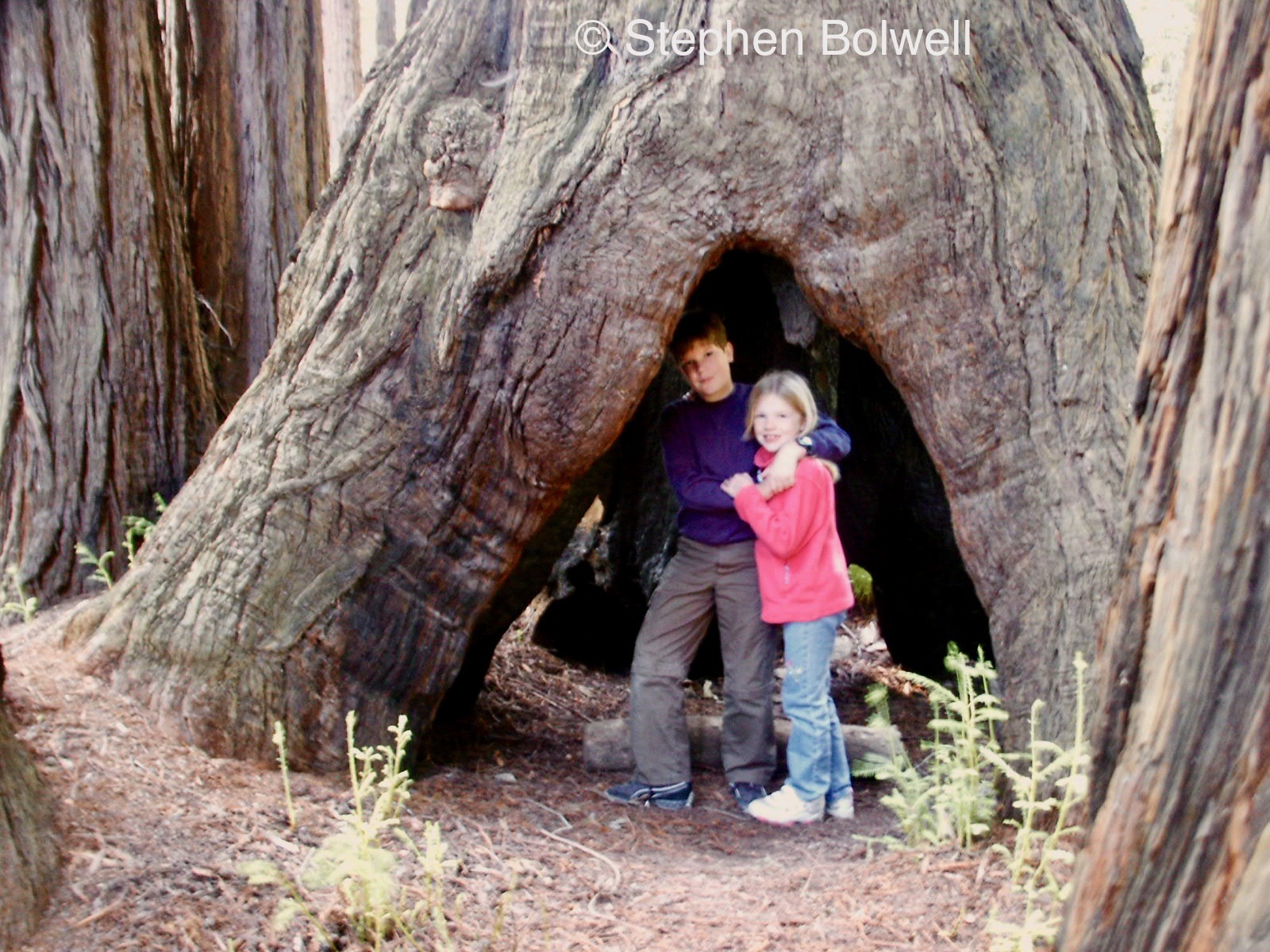

When my children were young, we took them on a road trip to California, driving the Pacific Highway from Los Angles to San Francisco before going east to visit Yosemite National Park. We then returned cross country to L.A. to visit Disneyland, this a thank you to the children for the terrible imposition of having to do interesting things. Although all of the information here, historical or otherwise, is written from the perspective of the present day, many of the pictures were taken during our trip.

Yosemite – The Battle for Survival.

In 1864 President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Land Grant giving Yosemite, along with the giant sequoias of the Mariposa Grove to the state of California. Galen Clark, one of the first non-native people to see the Mariposa Grove of giant sequoia, pushed congress to protect the area, and its preservation fell into his guardianship for the next 24 years. This was the first act of legalised conservation in North America and came 8 years before Yellowstone National Park was established in 1872.

John Muir was the first to witness and comment on the environmental problems facing Yosemite after it became a protected area. He made his first visit in 1868, and wrote extensively on a variety of issues that bothered him: the number of livestock grazing in natural meadows was troubling, particularly in the fragile upland areas; and there was extensive deforestation due to commercial logging in places where legal protection had been assured.

As has often been the case when attempting to protect natural habitats, it was a pen that brought effective conservation to the region. Muir wrote stories that focused effectively on environmental issues – and this worked as well back then as it does today – if a problem is clearly identified, whether it involves endangered animal species, or native trees standing in an exceptional landscape, a targeted approach will usually increase awareness and sway public opinion in a positive way.

With the help of Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of Century Magazine, John Muir continued to push for greater protection and the pair were persistently critical of the poor state of conservation management in the area. Their views would eventually prove instrumental in bringing about change with the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoia granted National Park status in 1890.

Muir and Johnson also advocated protection for other regions, in particular forested areas where giant sequoia were growing further into the Sierra Nevada. Eventually a number of these sites were selected for conservation, and Sequoia National Park was the result.

Unfortunately, greater legal protection didn’t solve the kind of problems that Muir had noticed and it wasn’t until he brought President Roosevelt for a visit in 1906 that things began to improve. Roosevelt, recognised the need for change and reacted quickly, taking back control of the region from the State of California in an effort to secure better protection, and the end result. ‘Yosemite National Park’… Nicely sorted and no further issues!?

Unfortunately, greater legal protection didn’t solve the kind of problems that Muir had noticed and it wasn’t until he brought President Roosevelt for a visit in 1906 that things began to improve. Roosevelt, recognised the need for change and reacted quickly, taking back control of the region from the State of California in an effort to secure better protection, and the end result. ‘Yosemite National Park’… Nicely sorted and no further issues!?

Well, not exactly…

Unfortunately, in recent years old trees in Yosemite have been dying in greater numbers than usual, and why has this grabbed the headlines? Because such trees have become dangerous to visitors, and knowing how litigious North Americans have become is an understandable concern. However, in wild places this is perhaps not the first problem that should spring to mind, because in wilderness areas trees left to nature will at some stage fall over, and management will always require a different approach from a city park.

Unfortunately, in recent years old trees in Yosemite have been dying in greater numbers than usual, and why has this grabbed the headlines? Because such trees have become dangerous to visitors, and knowing how litigious North Americans have become is an understandable concern. However, in wild places this is perhaps not the first problem that should spring to mind, because in wilderness areas trees left to nature will at some stage fall over, and management will always require a different approach from a city park.

The priority should be to ask why trees are dying in such large numbers in a national park, because if there’s a problem here, what chance is there of conserving trees that do not receive such stringent protection? Certainly it should not be assumed that trees standing outside national park boundaries only have value in terms of their worth to the timber industry.

The continuous whittling away of unprotected habitats has become a worldwide issue, because there is a misconception that the loss of natural forests can be easily remedied by simply planting more trees, but it’s not that simple; man cannot easily recreate ecosystems of the same complexity as those developed naturally over long periods of time. Much has been lost over the years with serious declines which makes it all the more important to pro-actively conserve all remaining environments of ecological significance. Just planting more trees is not the answer, better to allow natural forests to just get on with it which of course takes time. Trees should be allowed to seed and compete for their place in the future life of the forest, otherwise all we are creating is a botanical garden and not a natural habitat.

The continuous whittling away of unprotected habitats has become a worldwide issue, because there is a misconception that the loss of natural forests can be easily remedied by simply planting more trees, but it’s not that simple; man cannot easily recreate ecosystems of the same complexity as those developed naturally over long periods of time. Much has been lost over the years with serious declines which makes it all the more important to pro-actively conserve all remaining environments of ecological significance. Just planting more trees is not the answer, better to allow natural forests to just get on with it which of course takes time. Trees should be allowed to seed and compete for their place in the future life of the forest, otherwise all we are creating is a botanical garden and not a natural habitat.

There is a simple fix for the present rate of habitat loss and that is to halt the destruction; if we are to win the battle against species loss and global climate change it will require a significant shift in attitude to turn the tide. The state of our oceans should be the first priority, but conserving old growth forests runs a close second, and acting appropriately should be beyond the meddling of politicians who think they know better, with any attempt to curtail the necessary actions required to combat global warming beyond their remit as the situation has moved beyond the point where we can allow important decisions to made by idiots. Children get it, but politicians do not; they will always put economic considerations before the environment because that’s what gets them votes; but this prioritisation will quite evidently need to be reversed if we are to remain a successful part of the system.

Today, many plant and animal species have become stressed to their limits by environmental pressures, and Yosemite’s ponderosa pines are no exception; these trees are frequently infected by a tiny beetle, but years of co-evolution has allowed them to produce a defence in the form of a pitch that seals the beetles out. Unfortunately, there are other stresses weakening the pines’ ability to protect themselves; in particular five years of drought, this the likely reason so many Ponderosa Pines are losing their battle for life. As the trees defence mechanisms break down, natural resistance becomes compromised, and under the prevailing dry conditions, not if, but when a fire sweeps through, trees that might once have survived an intense burn, will no longer make it through.

Yosemite is one of the world’s great natural wonders, but when a single species goes into decline others living in association must surely follow. Such events are warnings that something is wrong – in this case a sudden change in climate which we ignore at our peril. Rarely in the natural world does anything decline in isolation; there is always a knock on effect, and you can’t help feeling that the dominoes are now being lined up in some of the World’s most beautiful places. We are now just waiting for the first one to go over.

The Coast Redwood and Giant Sequoia

North America contains many natural wonders, but wilderness areas to the west of the Rockies are amongst the most spectacular, and perhaps even more in need of protection today than they were in Muir’s time, because over the last 150 years so much has been lost or seriously degraded.

Much of the lands to the south and west had originally been Mexican territory, but in 1848 this land was ceded to the U.S. after the Mexican-American War. Accepting the extensive prairies of the mid-west, there was a general trend of deforestation in line with the wave of settlement, although going west in the early days didn’t necessarily mean coming over the Rocky Mountains and all the way to the coast.

Environmental problems could usually be linked to this flow of people from the east, in particular after the American Civil War which ended in 1865. Many were granted free land to the west, which had been stolen by government from native Americans and re-assigned to the new arrivals; this in part to defuse the possibility of more trouble between opposing factions on the opposite side of the country, where many people had not entirely accepted the war as over.

Environmental problems could usually be linked to this flow of people from the east, in particular after the American Civil War which ended in 1865. Many were granted free land to the west, which had been stolen by government from native Americans and re-assigned to the new arrivals; this in part to defuse the possibility of more trouble between opposing factions on the opposite side of the country, where many people had not entirely accepted the war as over.

As people flooded in, everything that they came across became either real estate or a golden opportunity for asset strippers, and always to the detriment of natural resources. This was the starting point for ‘The American Dream’ – to go west and make something of yourself – which was usually an environmentally destructive process, because people busy trying to make it in sometimes difficult circumstances, often failed to recognise the real treasures standing before them – although not for long. To the eyes of the new arrivals magnificent trees were regarded as lumber just waiting to be converted into something far more useful – $$$$$$$$$s. It’s the American way. The truth is that conserving wild places is a relatively new idea, because people didn’t start appreciating natural environments until they had both the leisure time to do so and the means to travel.

As people flooded in, everything that they came across became either real estate or a golden opportunity for asset strippers, and always to the detriment of natural resources. This was the starting point for ‘The American Dream’ – to go west and make something of yourself – which was usually an environmentally destructive process, because people busy trying to make it in sometimes difficult circumstances, often failed to recognise the real treasures standing before them – although not for long. To the eyes of the new arrivals magnificent trees were regarded as lumber just waiting to be converted into something far more useful – $$$$$$$$$s. It’s the American way. The truth is that conserving wild places is a relatively new idea, because people didn’t start appreciating natural environments until they had both the leisure time to do so and the means to travel.

In the face of climate change and environmental collapse some people are now beginning to wonder if this $ value approach to just about everything is paying off… but not all, many still chase the tantalising dream of trouncing nature for personal gain without the least concern for environmental consequences; but as even the stupidest amongst us are beginning to learn, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. The less discerning might eat for free, before moving on, but somebody will have to pick up a very expensive tab. The fact is (and this is an actual fact rather than a made up one, for those who think facts are a matter of opinion), it is far cheaper to deal with environmental issues before they get out of hand than after, and there’s always the possibility that beyond a certain point there is no going back in any case.

It is sometimes easier to spark enthusiasm for natural environments by favouring a key species rather than the ecosystems they are part of. Without doubt most of us appreciate that natural systems exist as complex webs of life; but our minds work better if we don’t complicate the issues; and there is no doubt that concentrating attention on a single plant or animal species works really well when it comes to raising awareness. Usually an animal will be selected to grab our attention, but once in a while an exceptional plant will do just as well, and when it comes to trees it is usually their magnitude and splendour that provides the wow factor, and the awe and majesty of the giant redwoods of the Western United States seldom fails to impress.

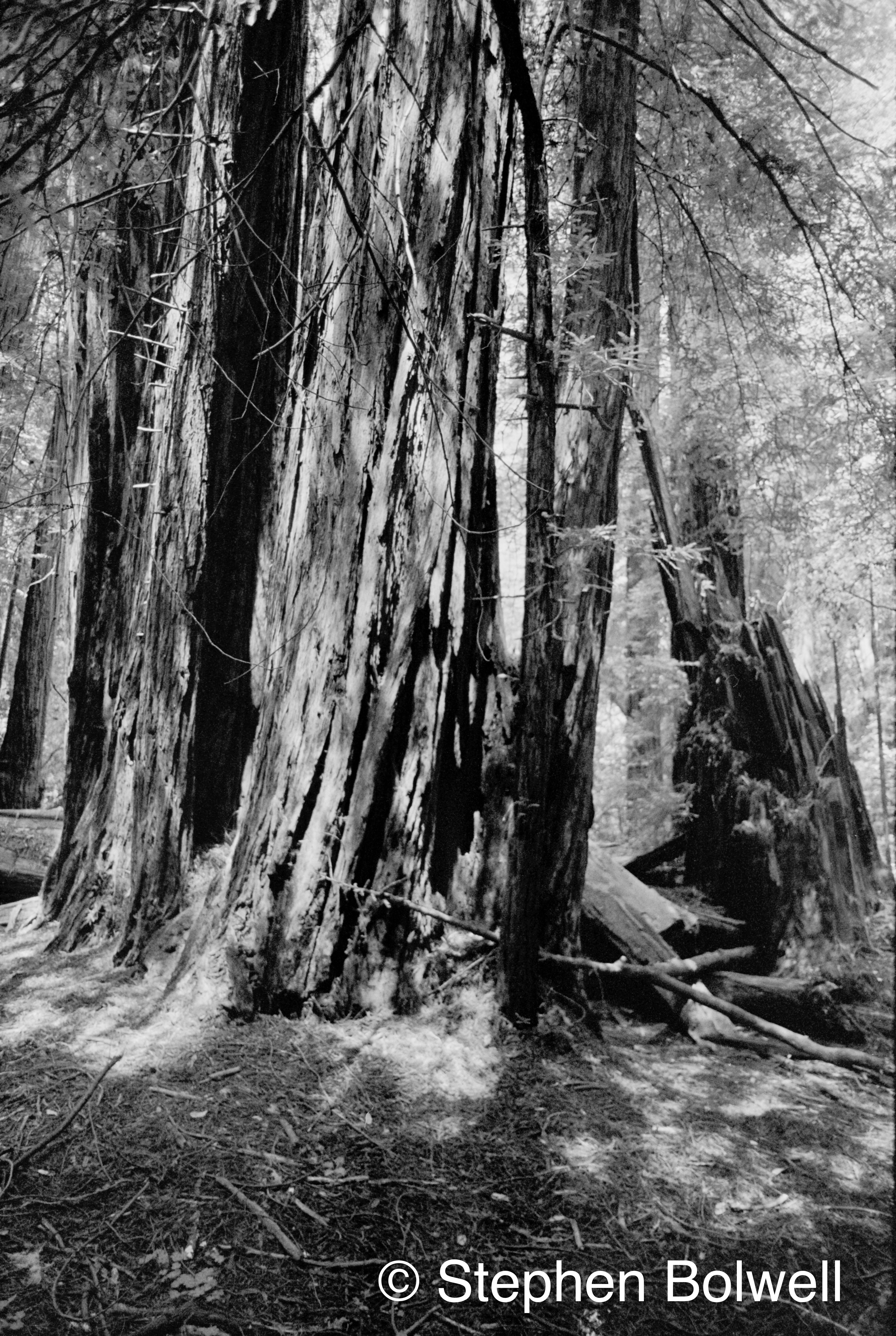

Old growth Giant Redwood and Giant Sequoias are so impressive they have become great ambassadors for the ecosystems they are part of. Their names are often used interchangeably, but despite certain similarities of size and appearance, these are botanically distinct species.

Redwoods were once widespread in North America but today are represented by only two species, each restricted to their own particular ecological niches in northern California. Plants however are not respecters of unnatural borders and redwoods may also be found in Washington State and Oregon, although outside of California they are found in lower numbers and are not naturally occurring.

Redwoods were once widespread in North America but today are represented by only two species, each restricted to their own particular ecological niches in northern California. Plants however are not respecters of unnatural borders and redwoods may also be found in Washington State and Oregon, although outside of California they are found in lower numbers and are not naturally occurring.

There is however a third representative, the dawn redwood Metasequoia glyptostrobides, and although fossil records demonstrate that this species was once widely distributed, and until recently thought to be long extinct, living examples were discovered in the Sichuan Province of China during the mid-1940s and suddenly they were back from the dead. This is interesting, but the Dawn Redwood is a long way, both in size and location from the species under consideration here: the ‘coast’ or ‘California redwood’ Sequoia sempervirens; and the ‘giant sequoia’ Sequoiadendron giganteum, are both referred to as Redwoods, and both are quite spectacular, with each contained within a very limited range.

A mature California or Coast Redwood will grow taller than a giant sequoia, but they are slimmer and less bulky in form and grow naturally only in one type of habitat: the moist, humid coastal regions of Northern California where sea fogs provide the damp conditions and moderate climate they require. These Redwoods tend to grow in bands rather than stands and do not occur naturally more than 50 miles inland.

Although most of the old growth forests are long gone, young trees now seem to be doing well, perhaps because in recent years there has been less fog, which hasn’t been entirely detrimental: with more sunlight getting to the trees there are greater opportunities for photosynthesis. But as with most living things, survival depends upon a range of circumstances: if say the climate continues to change and the mists become much less a feature of this region, the Coast Redwood might at some stage begin to suffer. It is clear that we change the climate at our peril and can never be absolutely certain of the consequences.

The Giant Sequoia is the only remaining species still living from the Subfamily Sequoioidae, it requires higher elevations than the Coast Redwood and grows along a comparatively narrow band on the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Living at an altitude of between 5 and 7 thousand feet these trees rely heavily on snow melt for water, and in summer, the dry heat of the region triggers the cones, mostly at the top of the tree, to open.

Giant Sequoia grow to more than 300 feet and in doing so will attain a considerable bulk. The General Sherman, the largest tree presently standing in the world can be found in Sequoia National Park, although it is not the tallest tree living on the Planet. The General contains more than 52 thousand cubic feet of wood and weights around 2.7 millions pounds, but typically, this is a species that does not reach the dizzy heights of the coastal redwoods which can reach around 375 feet, making them the tallest trees standing anywhere on Earth.

If you happen to be in San Francisco, coast redwoods are not far away, and if you travel east for about 170 miles to Yosemite National Park it is possible view the impressive Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias, which allows for a comparison of both native redwood species in a single day, although if you aren’t in a tourist inflamed rush it is perhaps better to take your time.

The bad news for redwood forests, is the same as it is for any other old growth forest that still exists along North America’s western seaboard. 95% of everything that was once standing here has been felled, and it has happened comparatively recently and over a very short period of time. Towards the end of the 19th Century, the continued influx of settlers from the East was enormously consequential as vast swathes of forest were steadily brought down, and ecologically significant trees still being felled to the present day.

The bad news for redwood forests, is the same as it is for any other old growth forest that still exists along North America’s western seaboard. 95% of everything that was once standing here has been felled, and it has happened comparatively recently and over a very short period of time. Towards the end of the 19th Century, the continued influx of settlers from the East was enormously consequential as vast swathes of forest were steadily brought down, and ecologically significant trees still being felled to the present day.

San Francisco was originally built from the timber of local redwoods, and although resins make the trees less susceptible to insect attack, the wood has a reputation for being brittle and some now consider processing them quite wasteful, claiming that it makes more sense to utilise other species more useful to forestry.

The loss of so much old growth forest is depressing, especially because giant old trees lock up such large amounts of carbon, and continue to do so even after they have fallen. Given that a coast redwood can live for 2,000 years and a Giant Sequoia for around 3,500, there’s not only a considerable amount of carbon locked up in a redwood forest, but it remains locked up for a very long time.

The loss of so much old growth forest is depressing, especially because giant old trees lock up such large amounts of carbon, and continue to do so even after they have fallen. Given that a coast redwood can live for 2,000 years and a Giant Sequoia for around 3,500, there’s not only a considerable amount of carbon locked up in a redwood forest, but it remains locked up for a very long time.

This is perhaps one of the best reasons for protecting ancient redwoods wherever they remain; and if many of the younger trees were left to grow to their full potential they might also act as valuable Carbon sinks and their presence have a moderating effect on climate. For these reasons alone it is difficult to argue against the conservation of giant redwoods wherever they are growing naturally.

It usually isn’t a good idea to plant a tree in the wrong place, but there are exceptions, and I will admit to having planted specimen coastal redwoods on the property we once owned on the North Island of New Zealand where the climate very much suits them.

Having specimens trees of different species gathered together in botanical gardens is of great value, not only to make direct comparisons, but also to preserve genetic diversity if wild populations should collapse, which is a real possibility; but it is wrong to plant trees that are invasive with seedlings growing to compete with native flora.

When in the U.K. this spring I took time to visit giant redwoods, red cedars and Douglas fir, all native to the west coast of North America where we now live. Most of the significant specimen trees along the Bolderwood Arboretum Ornamental Drive in the New Forest – Southern England, were planted in 1859 and still have quite a bit of growing to do, but despite this, the two tallest trees in the New Forest are a pair of giant redwoods that stand majestically on either side of a grassy ride. There are many examples of giant redwoods outside of California, as they grow well wherever conditions suit them. Seedlings of both species are readily available from commercial growers, but it is worth thinking to the future, and accepting that these are trees not ideally suited to a suburban garden.

When working for the B.B.C. a television producer once suggested that I might put headphones on and using a tape recorder play my favourite music in the hope of releasing some deeply hidden artistic potential as I filmed amongst the mighty sequoias, but I never did that… Experiencing Bach’s music in a magnificent forest is agreeable, but nothing can compare to listening to the wind blowing through the canopy – it sounds as if the trees are whispering. A romantic notion perhaps, but maybe the old redwoods are trying to tell us something about conserving the old growth forests of the west, but if that’s the case, we haven’t heard them over the buzz of the saw, or it might just be that we still aren’t listening.

Take care in Yosemite especially when trying to get a better picture, there have recently been several accidental falls and fatalities – it’s a wild place without unsightly barriers – so, please think safe.