It is commonplace for leaders in tropical regions to receive criticism for their inability to conserve natural forests, but in northern temperate regions politicians have not been made so directly accountable, and the felling of swathes of grand old trees has passed largely without comment.

West of the Rockies in the Pacific North West, there is a particular problem, especially in coastal regions where old growth forests have been felled without much concern for environmental consequences. The timber trade has played an important role in local economies since the arrival of Europeans and the resultant destruction of virgin forest has continued without pause for over 150 years, with a startling increase at the beginning of the 20th Century, as forests to the east were by then pretty much decimated.

The ecological importance of old forests in temperate regions has never been adequately considered, but given the longterm consequences of the loss it is difficult to understand why so little has been done to halt the widespread destruction. When it comes to forestry it is understandable that trees are measured by their $ value, and that makes big old trees an economic target.

However, the forests’ of the North West are important in a way that moves their significance far beyond making a fast buck, because the old growth forest here lock up more carbon than a comparable area of Amazon rainforest and this makes their rapid loss especially disturbing.

On the 23rd May 2019 Jen and I were in for a treat, visiting a group old trees in the Hidden Grove on the Sechelt Peninsula: at over 700 years of age, some of the Douglas Firs to be found here are impressive; today, few trees of this stature can be found without travelling some distance from our home on the Lower Mainland of British Columbia.

We started by visiting a lonesome tree that had somehow managed to avoid the saw, and still stands in the forest not far from the town of Sechelt. Our journey was undertaken mid-week and off season and things were agreeably quiet. Admittedly, going to gawk at a single tree seemed a little odd, and reminded me of a cartoon I saw in the 1970s featuring a queue of people waiting to see the last tree standing on Earth – it didn’t seem funny then, and is even less funny now – particularly in a temperate region of the developed world where people consider themselves well informed about environmental issues. Something is not quite right with old growth forest, because despite huge losses, old native trees remain inadequately protected.

Most of us will get upset when a large mammal species is threatened, but old trees growing in places other than tropical rainforest, don’t arouse the same concern, even when, as is the case for the Pacific North West, native trees are amongst the largest organisms existing on Earth. There are of course activists who tie themselves to significant trees to prevent felling, but few of us behave quite so proactively – we risk being labelled ‘tree huggers’, and that’s not a good look. Whatever our reactions, nothing can alter the fact that trees many hundreds of years old that were once an important part of human experience, are no longer standing in great numbers.

The indiscriminate felling blossomed in plain sight, a tragedy that either happened because people failed to notice, or felt powerless to do anything about it. The losses were certainly noticed in the early 1900s when there was concern throughout the North West over clear cutting without restraint; but a precedent had been set some 50 years earlier when railroad barons were gifted huge tracts of forested land to incentivise railroad building, putting much of the old growth forest into private ownership and with no legal protection the trees began to disappear.

Now, we clearly understand the importance of old growth forests to natural environments and their usefulness in locking up Carbon (some recent research suggests that older bigger trees capture more Carbon than do smaller trees); so why are big old trees still being felled? To be honest… I have no idea why anybody would do something so stupid, but the general indifference of the public at least, may be down to a general inability to distinguish between old growth and secondary forest, especially when viewed from a distance.

For most of us, trees are just trees, but in ecological terms their age has significance: old growth forest provide more environmental complexity than any secondary forest can achieve, unless the latter can remain standing for hundreds of years, which isn’t the way things usually go, as most trees are now harvested in cycles that run considerably less than a hundred years.

When areas re-seed naturally, they will one day become forest, but if planted selectively by man, things usually get worse before they get better, because it takes time for trees (acted upon by natural forces) to compete and eventually sort out which will ultimately become successful. When trees are planted for commercial purposes alone their ecological value drops significantly… yet we still keep thinking – there’s no shortage of trees, and in some cases that’s true, but many of the wooded hillside we admire are destined to have a short term existence: they’re entirely unnatural, lack diversity and create poor environments for other species.

When areas re-seed naturally, they will one day become forest, but if planted selectively by man, things usually get worse before they get better, because it takes time for trees (acted upon by natural forces) to compete and eventually sort out which will ultimately become successful. When trees are planted for commercial purposes alone their ecological value drops significantly… yet we still keep thinking – there’s no shortage of trees, and in some cases that’s true, but many of the wooded hillside we admire are destined to have a short term existence: they’re entirely unnatural, lack diversity and create poor environments for other species.

To those who are not much interested in environmental issues it is important to say that this is not a rant about saving every last tree in the forest; the logging of secondary forest planted specifically for cropping is necessary, and done properly it should allow the remaining old growth forest to be more easily conserved; but unfortunately, this isn’t happening and if we continue to lose old growth at the present rate, it is with the knowledge that once gone such areas cannot be easily re-created and as each disappears, so do the many organism associated with them.

Once the old trees have been felled close to places where we live – which mostly has already happened – but logging continues in out of the way places and less easily observed. Most of us remain clueless about the activity, with the losses having consequences to both ourselves and the natural world. If we were better informed, perhaps we would question the situation more thoroughly.

Any time a road comes near a natural forest, big trees that have commercial value will usually be targeted; clear cutting is usually the most economical way of getting them out, and this results in the complete destruction of viable ecosystems.

This disregard for nature has resulted in the loss of many great forests in a comparatively short time, causing widespread soil erosion, problems with water quality, and changing climates not just regionally, but across the Planet; and we’ve come to accept the situation without complaint or very much thought.

Visiting The Sechelt Heritage Hidden Groves. is for Jen and I like travelling back through time. Here a handful of ancient Douglas-fir still stand along with red cedar amongst a secondary growth of much younger trees. when left alone these species will achieve considerable age and reach an impressive girth and height. In short these are trees with the potential to grow as Donald Trump might say’ big league’, or is it ‘bigly,’ because ‘bigly’ really is a word that along with our moral judgements on big old trees, has fallen out of use.

Visiting The Sechelt Heritage Hidden Groves. is for Jen and I like travelling back through time. Here a handful of ancient Douglas-fir still stand along with red cedar amongst a secondary growth of much younger trees. when left alone these species will achieve considerable age and reach an impressive girth and height. In short these are trees with the potential to grow as Donald Trump might say’ big league’, or is it ‘bigly,’ because ‘bigly’ really is a word that along with our moral judgements on big old trees, has fallen out of use.

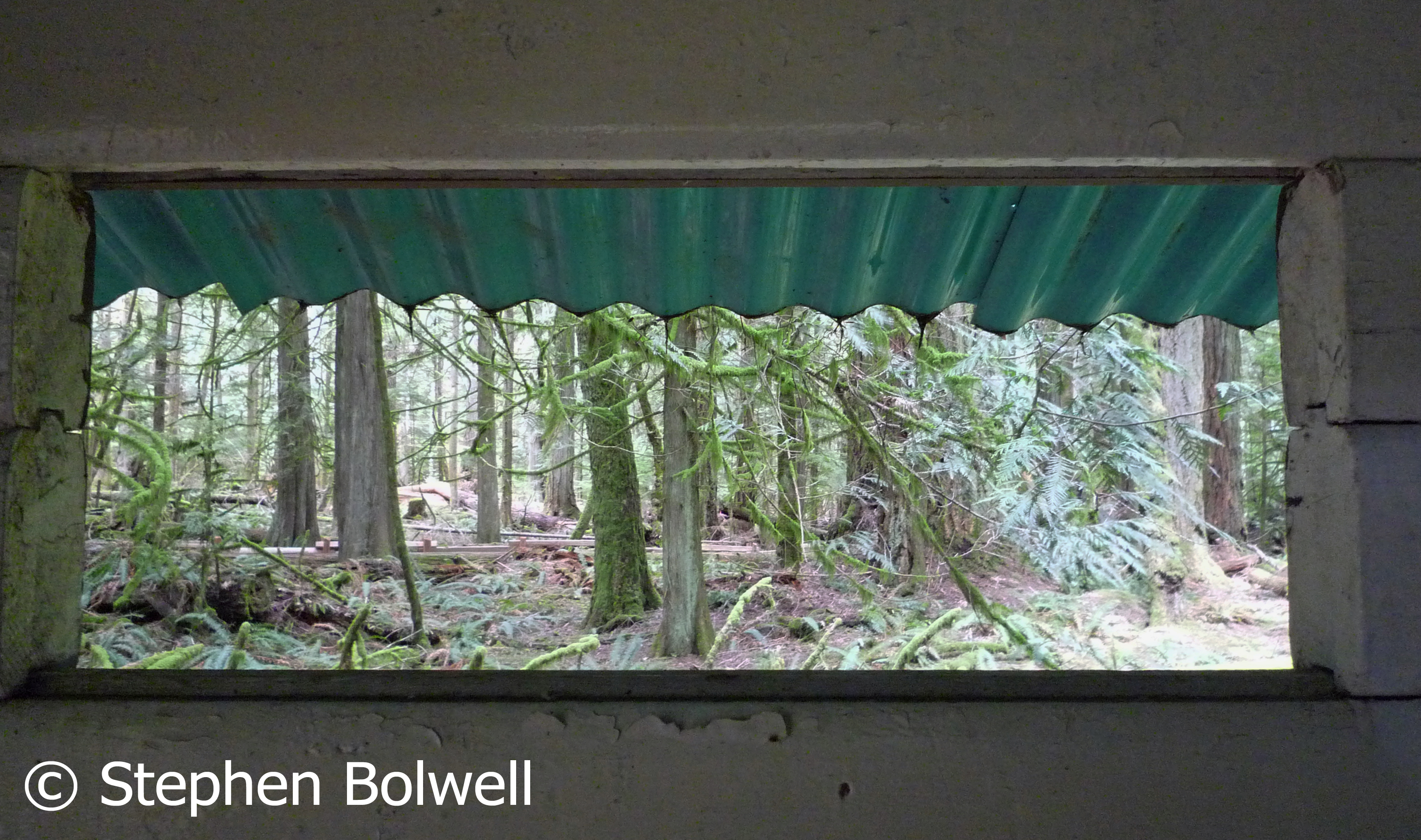

Beneath the canopy where we are walking the understory is lush with ferns, mosses and lichens. Close by, a maple wetland adds diversity and all is set amongst impressive rocky outcrops, but it is our arrival at a scattered stand of ancient trees that raises most interest, not just because they are majestic, but because their survival has been tenuous, and tenuous has become an all too familiar story.

In 2002 a local resident visiting the grove noticed coloured tapes in place, indicating preparations for the felling of what is now ‘The Hidden Grove’. A logging company was about to clear cut the few trees that remained here, destroying the last vestige of original native forest in the area, and at the beginning of the 21st Century this seemed extraordinary. There followed a protracted battle during which a group of local people worked diligently to keep the trees standing, involving thousands of hours of fund raising and voluntary work; but the persistent conservation effort paid off; and we are indebted to a small group of proactive people who suddenly came to the rescue, because without their efforts this majestic group of trees would no longer be standing.

This small grove of old growth Douglas Firs is comparatively small; and a resident of Sechelt told me they had survived only because the area had been too waterlogged to allow felling. I can’t find any definitive evidence that this is the case, but it does seem a reasonable explanation.

There are other stands of trees in the Sechelt area that have grown to an impressive size and those in the Hidden Forest are certainly impressive, but there are even bigger Douglas-firs in existence with girths that are nothing short of jaw dropping; however trees like this are few and far between and we must now make do with far younger trees, inferior in scale to those known to our ancestors… It is as if our destructive habits have steadily moved into line with our downgraded notions of awesome.

When an old growth forest is cut there is always a hope that the companies involved might leave a stand of old trees to maintain the integrity of at least a small area of original forest; but this rarely happens because any tree left standing would be considered a waste of valuable timber – essentially it is a question of perspective.

I have met commercial foresters who think that any tree left to grow old and fall over is a waste, whilst others regard a rotting tree as a valuable part of the ecosystem. Opinions aside, it’s worth remembering that estimates of tree cover are mostly done by those involved in felling them, and consequently figures are often skewed to demonstrate how much first growth forest remains. Large areas of bogland that contain stunted little trees are often incorporated into the figures; certainly these areas will not have been cut, but it is disingenuous to consider ‘bonsai trees’ first growth forest.

I have met commercial foresters who think that any tree left to grow old and fall over is a waste, whilst others regard a rotting tree as a valuable part of the ecosystem. Opinions aside, it’s worth remembering that estimates of tree cover are mostly done by those involved in felling them, and consequently figures are often skewed to demonstrate how much first growth forest remains. Large areas of bogland that contain stunted little trees are often incorporated into the figures; certainly these areas will not have been cut, but it is disingenuous to consider ‘bonsai trees’ first growth forest.

There is a lot of potential profit tied up in any tree that makes durable wood and grows to enormous size, especially when such a tree has been standing for five hundred years or more, locking up considerable volumes of heartwood, which greatly increases their value. Unfortunately, as the number of big old trees is reduced, quality timber becomes scarcer and increasingly sought after, and inevitably most will and be felled unless we put the long term environmental impact over short term financial gain.

There is a lot of potential profit tied up in any tree that makes durable wood and grows to enormous size, especially when such a tree has been standing for five hundred years or more, locking up considerable volumes of heartwood, which greatly increases their value. Unfortunately, as the number of big old trees is reduced, quality timber becomes scarcer and increasingly sought after, and inevitably most will and be felled unless we put the long term environmental impact over short term financial gain.

Few places in the world allow the felling of 600 hundred year old trees as a matter of course – such trees are clearly not a renewable resource in the short term. Now most of the old forests have gone from British Columbia, the new growth will not remain standing beyond a felling cycle of 60 or 70 years, a tenth of the time that would be required for a red cedar or Douglas fir to reach its full potential.

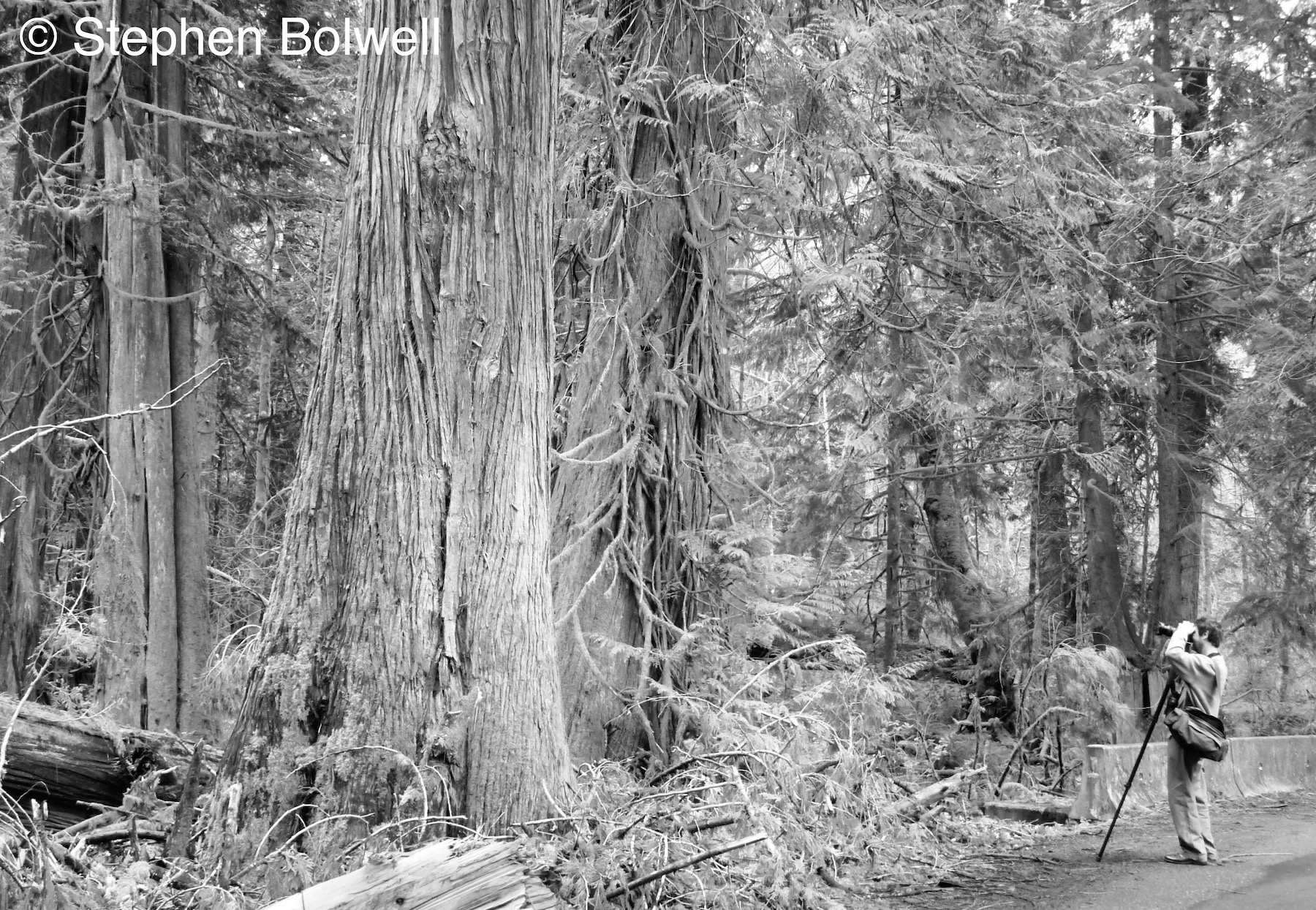

It understandable that some people will gain pleasure from seeing old tree, and certainly this was the case on April 20th 2013 when Jen and I crossed The Strait of Georgia to see an impressive grove that stands against the odds on Vancouver Island.

I had imagined Vancouver Island would have extensive virgin forests of giant Red Cedar and Douglas Fir; and prior to European settlement this was the case. But really, what must I have been thinking… bar a few remnants the grand old forests are gone. Only 20% of old growth forest are now thought to remain and why these are not protected isn’t clear, because forestry might easily be sustained from the 80% of productive secondary forest that remains. The fact that the old growth forest can still be cut is scandalous to some; because if this continues it is difficult to imagine how the remaining old forests can be preserved, with less than 10% existing under the protection of National Parks.

I had imagined Vancouver Island would have extensive virgin forests of giant Red Cedar and Douglas Fir; and prior to European settlement this was the case. But really, what must I have been thinking… bar a few remnants the grand old forests are gone. Only 20% of old growth forest are now thought to remain and why these are not protected isn’t clear, because forestry might easily be sustained from the 80% of productive secondary forest that remains. The fact that the old growth forest can still be cut is scandalous to some; because if this continues it is difficult to imagine how the remaining old forests can be preserved, with less than 10% existing under the protection of National Parks.

Cathedral Grove is located in a central forested region on Vancouver Island and over the years has attracted a great many visitors. This small remnant of old growth forest is made up predominantly of Douglas-fir and red cedar. The trees here are more than 800 years old and there is a striking parallel with the trees in the Hidden Grove, because not only have these trees escaped the saw, they are also survivors of a great forest fire, in this case one that passed through the region more than 350 years ago. It is nevertheless more recent attempts by lumber companies to fell them that has proven their greatest challenge. Today felling any tree close to the grove would be bad news because big trees that have grown most of their lives in forest need protection; when exposed they become vulnerable, particularly from high winds; trees growing around them will provide shelter, even when such protectors are a quarter their age or younger still.

The most recent challenge to the Grove came at the turn of the Century when a section of surrounding forest was logged: this might have been expected at the end of the 19th Century when old growth forests were being felled at an extraordinary rate, but these trees were felled at the end of the 20th Century which in more enlightened times seems almost unbelievable.

When I first came to live in B.C. I assumed Vancouver Island’s old growth forests far too consequential to have been logged out, but that was silly, because ‘logging out’ is more or less the way things have been heading since European’s settled – it seems to have been regarded as a fundamental right to chop down almost any big tree regardless of the environmental consequences. Ken Wu Executive Director of The Endangered Ecosystems Alliance states that since 1993 more than 250,000 hectares of old growth forest has been logged on Vancouver Island – an area more than 20 times the size of the City of Vancouver.

There is however some hope, but legislation would be required to bring change, based upon the research of a group at The University of Victoria which is calling for the greater protection of British Columbia’s naturally growing trees.  The recommendation is that that 30% of the Provinces old growth forests should be protected; although deciding where to start measuring from is tricky: should it be 30% of the whole island’s remaining cover, or 30% of the natural cover that was present before European’s arrived. 170 years ago most of the land in the Pacific North West was almost entirely covered by forest; if it is 30% of what now remains, then once again it will be slim pickings for the natural world. Personally, at the rate of loss so far experienced we might consider ourselves lucky to get anything at all. The report however is unambiguous, it recommends that 30% of the original old growth forest should be conserved despite much of it having already been felled; it sounds like something from our wildest dreams, because to regrow what was originally present would require a project that runs successfully for hundreds of years. Nevertheless it is impressive that a science based group is sticking their necks out, by saying that it is necessary and should be attempted.

The recommendation is that that 30% of the Provinces old growth forests should be protected; although deciding where to start measuring from is tricky: should it be 30% of the whole island’s remaining cover, or 30% of the natural cover that was present before European’s arrived. 170 years ago most of the land in the Pacific North West was almost entirely covered by forest; if it is 30% of what now remains, then once again it will be slim pickings for the natural world. Personally, at the rate of loss so far experienced we might consider ourselves lucky to get anything at all. The report however is unambiguous, it recommends that 30% of the original old growth forest should be conserved despite much of it having already been felled; it sounds like something from our wildest dreams, because to regrow what was originally present would require a project that runs successfully for hundreds of years. Nevertheless it is impressive that a science based group is sticking their necks out, by saying that it is necessary and should be attempted.

‘Beautiful British Columbia’ is what a lot of us have written on or number plates which demonstrates a certain unwitting hypocrisy because most of the Provinces ancient native trees are afforded no protection outside of National Parks. The first Douglas-fir Pseudotsuga menziesii ever recorded was discovered on Vancouver Island by Archibald Menzies in 1791, but it was his rival David Douglas who recognised the tree’s potential as a timber resource, although the popular name is wrong – it isn’t a fir, or a spruce, or even a pine, it is a false hemlock. This is the tree that many of us will use as a Christmas tree, but when fully grown the coastal variety is the second largest tree species in North America after the giant redwoods found further south and perhaps best represented in California. An entire industry was built on felling the virgin forests West of the Rockies and sheltered coastal areas like Vancouver City grew to prominence distributing this valuable resource.

I have heard older people who have made their living from felling these incredible trees, say that if they hadn’t chopped them down, we’d all be walking around in the dark interior of a forest… but age isn’t always a measure of wisdom… because of course we wouldn’t. Certainly a lot of trees would have been cut for commercial purposes, but there was never any obligation, or entitlement to destroy a whole natural ecosystem just to keep us out of the shade. Undoubtedly, it is more about pocketing money and less about a fear of the forest that has driven the industry to fell so much of the original forest. An unfortunate combination of greed and ignorance has brought us to this unacceptable situation and we’ve labelled it progress – who would want to get in the way of that?

If we are thinking straight it isn’t difficult to come to the conclusion that the preservation of old forests has enormous value because the losses have put natural ecosystems under threat, and that’s before we start worrying about the water table and climate stability – all of which are essential to our continued existence. If we continue to view the natural world as something to be destroyed purely for economic gain, then we are in for a hiding. You don’t need to be very clever to exploit natural resources to make money, but when they run out and you’ve screwed nature into the bargain, something has to change.

In future big countries with enormous resources, without exception will need to find more inventive ways to run their economies. People who make their livings by directly exploiting whatever the land has to offer are not inclined to change their approach, but this is lazy thinking and they are going to have to. Before we start considering about all the different technical ways we might lock up Carbon we should first consider the Carbon scrubbers that nature has already provided, they’re called trees and the present rate of Worldwide clearance makes no sense. People who wish to continue to mercilessly take advantage of the environment in the present climate (quite literally) have not yet touched base with the present reality. In the case of Canada (given as an example only because this is where I presently live), one future industry that continues to develop is tourism, and it seems counter productive to continue destroying the very environment that people come to see that’s moose, beavers, bears and big old trees.

In future big countries with enormous resources, without exception will need to find more inventive ways to run their economies. People who make their livings by directly exploiting whatever the land has to offer are not inclined to change their approach, but this is lazy thinking and they are going to have to. Before we start considering about all the different technical ways we might lock up Carbon we should first consider the Carbon scrubbers that nature has already provided, they’re called trees and the present rate of Worldwide clearance makes no sense. People who wish to continue to mercilessly take advantage of the environment in the present climate (quite literally) have not yet touched base with the present reality. In the case of Canada (given as an example only because this is where I presently live), one future industry that continues to develop is tourism, and it seems counter productive to continue destroying the very environment that people come to see that’s moose, beavers, bears and big old trees.

On our return to the Lower Mainland, the lack of anything that resembles old growth forest is jarring, because none remain standing – the last having been cut within living memory.

This coastal strip has a generally fertile soil and as Europeans settled in greater numbers, forests were quickly cleared for agriculture; and more recently much of this has been covered by urban development.

It seems ironic that some of the biggest trees ever to grow in British Columbia once did so on the Lower Mainland, where no old forests can be found today. But here, in the small areas of secondary forest that have been left for their ‘amenity value’ (a euphemism for ‘somewhere to smoke cannabis and empty the dog), the occasional big old rotting stump is a stark reminder of a recently lost majesty that once ran from the mountains to the sea.

We all have an idea of what an old growth forest should look like, but few of us have the opportunity of such an experience, because opportunities are now so few and far between.

Should you come to the North West Coast, you might be lucky enough to stand in a remnant of virgin forest, or perhaps just get to see a very old native tree… If you do, then please take a photograph as a reminder of how things used to be, because outside of National Parks there is no guarantee that the next time somebody visits, that wonderful old tree will still be standing.

Please take a look at this link:The great bear loophole. Why Old Growth is Stil Logged. We are often led to believe that forests are being protected when they are not. This problem occurring in many places around the world and it is important that we are aware of the situation; because our futures may be in jeopardy if we don’t halt the felling of old growth forests – especially in protected areas.