During a recent visit to Belize with my wife and daughter, it was impossible not to appreciate the beauty of the flora and fauna of what many regard as a a sub-tropical paradise. “But, there is something missing”, said my wife, “and I’m not sure what it is”. I thought about this for while and if I had to put it down to one particular thing, then it would have to be a lack of primary forest.

Figures for deforestation are sketchy for Belize and what we believe sometimes depends on where the figures come from – certainly it would be disappointing if the generally accepted figure for loss really is running at 2% per annum.

There are also stories that give cause for more general concern. It is said, for example, that during the 1990s the Belize government granted unusually low logging concessions to a Malaysian company – rights were purchased for as little as 60 cents an acre… It defies belief that such a story could be true, although such indifference to a valuable national resource seems almost too ridiculous to make up.

When forest depletion figures are presented for tropical regions, the details are sometimes misleading. Many logging concerns are intent on getting into virgin forest where the real value lies in big old hardwood trees, which can now fetch astronomical prices. Companies that are cutting into these diminishing ecosystems are less inclined to bother with the lower value smaller trees growing back in secondary forests, i.e. places where trees have been logged in the past. The point is that it is essential to know exactly what kind of forest is being logged to truly understand the consequences. Foresters will sometimes say that for every tree they cut two more will be planted (I was told exactly this in relation to mahogany trees during our visit to Belize), but it doesn’t mean anything unless there are exact details on the age and size of the trees being felled. Replacing a 30 year old tree in a secondary forest with two replacement saplings is one thing, but hardly a replacement for a 300 hundred year old tree cut in primary forest? From an ecological perspective and in most other senses there is an enormous difference and we should all be concerned because the loss of forests containing mature old trees will have far reaching consequences.

A positive case is often made for selective logging rather than clearcut felling an area, with only certain trees taken out; but it is difficult to imagine how anybody could make this version of habitat destruction sound like a really good idea.

However, there are people in the conservation ‘game’ who claim that cutting out all of the large mahogany trees in an ecosystem makes no difference to the health of a forest, but how can they possibly suggest that? Maybe they simply take a walk in the forest, have a bit of a look around and decide that if you didn’t know the trees had been felled, then maybe you wouldn’t notice a difference despite the fact that mahogany trees, where they do remain in place, play a consequential part in their ecosystems. It should be obvious that the removal of a single prominent species, which other plants and animals inevitably rely upon, cannot be undertaken without consequences.

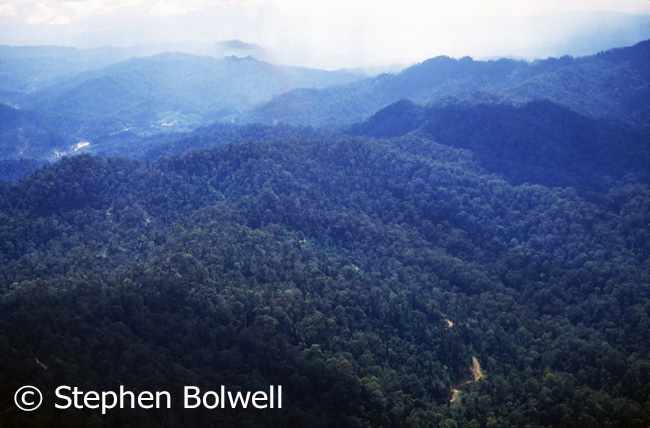

To log an area successfully requires the cutting through of logging roads and once they are in place they quickly become a magnet for illegal loggers. In particular, I have noticed (from the air), how quickly Malaysian rainforest disappears once it has been made accessible.

Felled trees can only leave a forest efficiently when tracks are extensively cut in. The felling process, no matter how selective, is always destructive; and the idea that taking out only the commercially valuable older trees can be achieved without changing the optimum natural functions of a forest is difficult to argue.

Visiting Coxcomb Wildlife Sanctuary in the Stann Creek District of south-central Belize was nothing short of delightful, even though logging would have been a feature here from the late 1930s through to 1988, when buildings previously owned by the logging company were taken over to form the park’s visitor centre. This should be a clue as to why so much of the surrounding forest is secondary and only recently regenerated. In fairness to any logging concern The Stan Creek District was seriously hit by Hurricane Hattie on October 31st 1961. Hattie is said to have taken out as much as 70% of the mahogany trees in the area and this is probably the main reason that logging came to an end – it is likely that there just weren’t enough big trees left standing to keep a commercial concern in business.

Whatever the reason for the loss, there were no extensive stands of original lowland forest apparent in any part of the park that we visited. But, this doesn’t mean the reserve isn’t an extremely important conservation area, in particular for the preservation of jaguar, essentially the reason that the park was set up in 1984. The regenerating forest still has enormous ecological value even if the surrounding habitat is a shadow of its former self, brought about by extensive logging and then almost complete destruction by Hurricane Hattie.

I must admit to being concerned when I see quotes about a secondary forest that has been around for perhaps only 30 years, when claims are made that the area has now completely regrown. This demonstrates a clear misunderstanding of tropical forest regeneration. Virgin forest that has been felled in recent time will not be just dandy again after the passing of a few decades and might never carry the same biodiversity again.

This white-collared manakin photographed in the bird heaven that is Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary likes to hang out in dense forest. It pings around like a pinball and will suddenly judder to a halt in display. This bird is completely nuts – it makes a loud noise exactly like marbles being bashed heavily together and remarkably it does this using its wings.

During our trip my daughter Alice was looking for adventure and could not resist the opportunity to zip line through tropical forest and rappel down a tumbling waterfall. She’d done her research and discovered in Mayflower Bocawina Park an adventure centre that could provide such opportunities only a short distance from our coastal base in Hopkins. While she was doing that, Jen and I took the opportunity to wander through the park’s secondary forest.

During our trip my daughter Alice was looking for adventure and could not resist the opportunity to zip line through tropical forest and rappel down a tumbling waterfall. She’d done her research and discovered in Mayflower Bocawina Park an adventure centre that could provide such opportunities only a short distance from our coastal base in Hopkins. While she was doing that, Jen and I took the opportunity to wander through the park’s secondary forest.

When we first entered Mayflower Bocawina National Park I noticed a wide track that had been cut along the border of the reserve. On arrival at the ticket office I asked why the trees had been felled in this manner and was told this had been done to mark the park boundary, but I wasn’t convinced, boundaries of national parks rarely involve habitat destruction, in particularly because some tropical forest species prefer not to cross open ground.

I began looking for somebody who might provide a more likely explanation as to why a swathe of trees had been felled through the forest and eventually came across a man who was clearly knowledgable about the reserve and its wildlife; he worked in the park, but not for the park and told me that this was a government sanctioned forestry project. He said that a logging road was being cut through to the back of the reserve in order to remove valuable teak trees. I do not have a secondary source to confirm this, but it doesn’t sound impossible as I’ve witnessed trees being removed from protected forest habitats before, both in Malaysia and Central America – in some cases with official stamps that falsely claim that the trees have come from a sustainable source. I can’t say for certain that teak trees will be coming out of the forest here and even if they do it probably won’t be illegal. It is just that such a thing is not unusual, which is disturbing, because while many of us obsess over the potential loss of an animal species that we are fond of, we are less inclined to be quite so pro-active about the disappearance of the habitat our favoured animal lives in. The felling of any quality primary tropical or sub-tropical forest, legal or not, is disturbing and already hugely consequential in terms of world weather patterns, soil erosion and the damage it causes local economies, let alone the more obvious problems of habitat and species loss.

Primary forest is essential to the survival of complex ecosystems – it can for example provide a habitat that is a couple of degrees lower than nearby regenerating secondary forest. If all that is left to us by continually opening up the interior is a pale washed out version of the original then we should balance short term economic gain against long-term environmental consequences. Sadly, we may let this pass without fully knowing what has been lost because we are recording so little of the virgin forest’s biodiversity before it is gone. Doing the right thing usually runs second to making a fast buck, which is both shameful and morally unjustifiable.

If a species disappears from the forest and we aren’t there to witness it… didn’t even know that it existed… does it really matter? This is not a philosophical question. It of course matters and it also matters that in future people will remain poorly informed as to what has disappeared; more especially because we remain indifferent to many less glamourous species despite their ecological importance. We will be ignorant of what natural environments were once like – of what has been lost in the same way that few of us have any idea what it was like before the time of manufactured pesticides… ignorance is bliss, but this ‘not knowing’ comes at a price, and for life on Earth that price might be a heavy one. With this ever increasing loss of habitat and by association, loss of species, our own continued success is thrown into question because we are not independent of the system – we are part of it.

If a species disappears from the forest and we aren’t there to witness it… didn’t even know that it existed… does it really matter? This is not a philosophical question. It of course matters and it also matters that in future people will remain poorly informed as to what has disappeared; more especially because we remain indifferent to many less glamourous species despite their ecological importance. We will be ignorant of what natural environments were once like – of what has been lost in the same way that few of us have any idea what it was like before the time of manufactured pesticides… ignorance is bliss, but this ‘not knowing’ comes at a price, and for life on Earth that price might be a heavy one. With this ever increasing loss of habitat and by association, loss of species, our own continued success is thrown into question because we are not independent of the system – we are part of it.

Whilst Alice ‘does her thing’, dipping through waterfalls and zipping through the forest canopy, Jen and I wander through the park. I grab shots of birds and butterflies as we walk towards yet another waterfall – a focal point that motivates us to keep going through the intense heat and high humidity of a muggy afternoon.

As we move along we see very few old trees, but there are many plants regenerating through scrubland that must once have been farmland; native species are now fighting their way back through cultivated forms such as banana and palm oil which are just about managing to hang on. It is also remarkable how resilient some animals are to living in environments that aren’t quite right for them, but that won’t be the case for every species and a price will have to be paid for the decrease in natural diversity that we have imposed.

If you ever get to travel through a tropical forest that has never been felled, then take the opportunity to make a photographic record of whatever you see because this might one day prove a useful record of potential losses. Unfortunately, I have returned to some rainforests areas only to discover that they have disappeared altogether. It’s always worth taking pictures of anything that seems interesting, especially if the time and place are carefully recorded. Now and again a good picture might turn out to be more important than it seems at the time… and who knows, one day it might help to save the Planet, or at the very least aid in species reintroduction – when we finally wake up to the dangers caused by the wanton destruction of valuable ecosystems.

Next: MayanTemples and Howler Monkey Business.