Well… Maybe.

A photograph can be targeted to help save the Planet, or more precisely, benefit present bio-diversity, but what about a painting? Perhaps a painting can provide a more imaginative approach and demonstrate truth more effectively than photography. Our minds relate to stories and a photograph sometimes tells a good one, but paintings can be honed more precisely – nothing need be left to chance – creating an image that really sticks in the mind.

When a few years ago I started photographing eagles on a local nest where generations of birds have reared their young for as long as anybody can remember, I wasn’t expecting such a rapid urbanisation of the surrounding area.

A chat with a local resident who has lived here for many years brought home a truth that can only be told with the benefit of time. Once there were six pairs of eagles nesting close by and now we are down to a single pair. Continued runaway development across the Lower Mainland of British Columbia is responsible for the declining availability of eagle hunting habitat and threatens the longterm survival of nest sites. This is important because disappearing eagles are indicators of failing ecosystems. In another environment some other animal will carry the banner for species diversity and a reliable measure of the health of our planet.

As usual, my story starts elsewhere. Some years ago I was filming during February at The Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, and each day I walked the short distance from my hotel to work. Then, one morning, a sudden gust of wind took my breath away, causing a severe pain in the nerves of my teeth and drove up through my head. I had the sudden impression that my eyeballs had frozen open and imagined myself as a cartoon character in icy motionless mid-walk, about to shatter into a thousand pieces, although in reality I’d made it through the museum doors.

As I was thawing out, I asked a professor how people survived days like this when temperatures dropped well below -20C; I never established exactly how low because nobody wanted to discuss that. He said, mostly, it was about dressing appropriately, but when things got really cold they just didn’t go outside.

Weather in Canada it seems is not simply a question of the wrong clothes, there are days when you could end up a stiff no matter what you are wearing.

Is it any wonder that the mild southern coastal area where I live is so popular. I am one of many outsiders who don’t have the cold tolerance of most Canadians who live in the interior – for more than half the year, winter temperatures fall lower than anything you could experience by sticking your head in the icebox of your fridge.

The mild Lower Mainland is caught between a rock, a wet place and another country and three things happen when space is limited: people move in, house prices go up and developers make money, but this isn’t a longterm reality because urbanisation can’t continue indefinitely – eventually space runs out and the environment in which we live becomes degraded. And it doesn’t make sense to build on the only location you have for food production with a reliably long growing season.

Worldwide we have colonised the most habitable regions and are increasingly disinclined to share with other species even when they benefit our general wellbeing. Our indifferent attitude to nature is a bit like strangling the canary before going into the mine instead of bringing the bird chirping along with you.

Eagles are at the pinnacle of a wide range of less charismatic creatures that go largely unnoticed, they are representatives of whole ecosystems, but once you move beyond using an eagle photo to ask ‘Will they stay or will they go?’ their image can so easily end up as just another agreeable wildlife picture. So, maybe there’s a more startling way to make a point… With a painting.

The claim that painting is dead has reoccured with great regularity over the years, because technology is always moving forward, creating a dazzling array of new ways to make images.

During the 1990s artists became increasingly indulgent – like naughty children they wanted to shock, but the only real shock was the employment of artisans to do their work for them. Then there were the naval gazers. ‘Look at me’, they bleated – ‘I’m full of angst and want to tell my story’. Fortunately, self analysis is no longer cool and science backs up the view that too much introspection is bad for us – looking outwards is far healthier. And then there are the artists still painting fruit bowls and goldfish… Is is any wonder that so many commercial art galleries are empty?

Art is usually related to the period in which it is produced and ‘now’ couldn’t be a better time to show ourselves as part of nature, rather than living above and dominating it. We can no longer ignore the havoc we are causing and this should be reflected in the art we produce.

Certainly landscape painting is of its time, although in the past it has either romanticised the natural world, or glorified the changes that humans have made.

John Constable’s ‘Hay Wain’ is amongst the most famous and seriously underrated paintings ever made; its artistic reputation steadily eroded over the years to the level of chocolate box art.

Our understanding of the painting has been seriously skewed by the passage of time. Apart from the course of the river Stour and the usual wild Constable sky, everything else is a construct of man and we might do well to reassess it with the benefit of the passage of 200 years.

Constable moved trees and buildings for artistic convenience, but still he painted a certain reality. Sadly I can’t paint as well as he did; I can’t even copy his technique – he sparkled the surface of his oils with white flecks that are difficult to emulate.

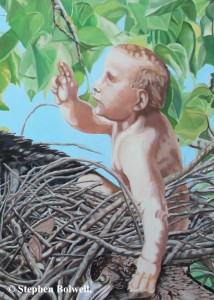

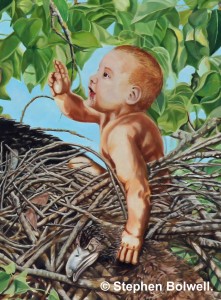

My paintings aren’t in any case a reality; they are allegories that examine our relationship with the natural world. ‘The Mixed Blessing’ was painted under the influence of place; it would not exist if I lived outside of this land of eagles, and relates directly to a moment in time.

On one level the baby represents us, and the eagles, the natural world. On another level the baby might be Jesus giving a blessing, and careful examination indicates that the blessing is not all that it at first seems.

Close to the beginning of the Old Testament God says ‘Let man have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air and over the cattle and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creepeth on the earth.’ Genesis 1:26. The King James Bible – a book that would be much shorter if God had been less inclined to repeat things.

At 1:28 God expands his instructions. ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth on the earth.’ This, all too spookily, is a description of our present behaviour. Maybe it’s a co-incidence – perhaps we’d be doing the same things even without God’s rule book, but as a directive – under the present circumstances, the ‘dominion over’ approach is seriously misguided.

I am not concerning myself with either God’s will or his existence, the point is that societies based upon Judeo-Christian foundations adhere to certain doctrinal behaviours, often long after their religions have faded, and that may not be a good thing.

THE STORY OF THE PAINTING.

I’ve painted Jesus as a baby before. I say painted, but all I did was copy ‘Virgin on the Rocks’ by Leonardo Da Vinci. I had two choices because Leonardo painted the subject twice. His first effort hangs in the Louvre and was intended for a church that was paying him a pittance. Leonardo sold it off quickly to another buyer, then rather insultingly took ages to knock out the second painting to fulfil his agreement – this now hangs in the National Gallery and the version I copied to form part of a much smaller painting. It was copied many years ago when I was a student (of Zoology – not art, so I won’t make any false claims about technique!)

Baby John is next to Mary and she is introducing him to Jesus – he is the baby sitting next to the angel to the right, and he is clearly giving a blessing – the action I wanted in the ‘The Mixed Blessing’, because anybody who has a background in art would get the reference straight away, but for most of us this doesn’t matter. Essentially I kidnapped this baby from the National Gallery’s version of ‘Virgin on the Rocks’ for a second time, and spent several days changing the tonal quality of the image to match the ‘all sweetness and light’ sunday school illustrations of childhood.

Then my wife saw the painting and told me, ‘this isn’t a baby… it’s a little old man.’ And because she works with babies I was forced to take note. ‘What do you mean…This is Leonardo Da Vinci, we’re talking about’, I told her, but a response based upon experience rather than art was difficult to argue against, and she wasn’t finished. ‘I don’t care who we’re talking about… He can’t paint babies!’, and she was right… I wonder how many art experts have noticed this. Maybe Leonardo couldn’t bring himself to render either Jesus or John as anything other than self aware and not in the malleable clay of infancy. – even as babies he could see only spiritual wisdom.

I felt my choices narrowing, and so it came to pass that the baby in the nest moved into the 21st Century, and perhaps this was for the best.

If there had never been a Genesis version of ‘In the beginning…’ would we think differently? Or, with the real possibility of a genetic predisposition to believe, might we have travelled another route to the same conclusion: God/us/the rest of life on Earth?

Without the option to rewind time, there is only scientific evidence to draw upon and this indicates we behave better when we think we’re being watched! Would overcoming this hardwiring in our brains allow us to see with more clarity how things really are.

Could we accept the blindingly obvious? We are clever animals but only in comparison with all the other animals – our brains have limitations. If we accepted that, might we be more inclined to see ourselves as part of, rather than above the natural world.

The ‘sole dominion’ approach clearly hasn’t been a great success in terms of the Planet’s biodiversity, and presently we need to chose diversity over dogma. Maybe it’s time to try something else… Humility perhaps? We might be stuck with faith, but a little logic wouldn’t go amiss; and if we can’t trust ourselves to live without a rule book, then at the very least the rules need to be updated once in a while in the light of new and reliable information.

And God said, ‘Go forth and be at one with nature’.

If we have to believe something – why not give that one a go. Sadly I’ve lost the Biblical reference, but it has to be in there somewhere.

With thanks to Dorcas for reminding me that God can be a difficult subject to discuss without upsetting somebody.

Other paintings by Stephen Bolwell can be seen at: agilispictures.com