The coastline of the Lower Mainland of British Columbia is a great place to watch birds — particularly ducks, geese and waders. As winter approaches, large numbers migrate through the region on their way south to warmer climes — and who can blame them? The hardiest find the many beaches and inlets of the region mild enough to overwinter, and unless temperatures drop to extremes they appear disinclined to expend their energy by moving further south, . In spring the birds will fly in the opposite direction, returning to their summer breeding grounds, and in doing so will cover enormous distances.

The event reminds me of the Wildebeest migration around the Serengeti Plain in East Africa, but there are obvious differences.

Presently, over a million blue wildebeest and around two hundred thousand zebra travel up to 500 miles on a yearly cycle around the Serengeti in East Africa. Essentially the animals follow the rain; or put another way, they are moving on to fresher grass as it begins to show. I witnessed the migration when numbers were higher than they are today, but the event is still the most impressive migration of mammals on Earth.

The bird migration I can witness closer to home; it involves millions of individuals travelling along the ‘Pacific Flyway‘. Some birds even fly right over my house. These journeys along the western coastline of the Americas are impressive, and not just because I can watch T.V. and look out of the window and witness the event. There’s an advert on television promoting BBC World; to the right of the screen ‘on sky’, there are geese skeining across in great numbers. Three birds have become detached from a V formation and I go outside to watch. It’s getting dark, I can hear the birds plaintively honking and the main group suddenly swings a little to the right and the lonersput on a sprint, cut across the angle and catch up. It’s more dramatic than watching television, but there’s no cut to the close up, the geese just keep going until they are too small to see — I wonder how they keep going, the expenditure of energy must be enormous, but standing out in the cold to consider such things seems pointless… I go back and sit on the sofa.

The migrating birds exhibit similar patterns of behaviour to the wildebeest — both groups are following the food and seeking out better conditions. It would be unfair to say the Serengeti event pales by comparison, but the numbers of birds and the distances they travel are in a different order of magnitude — and as long as their journeys continue, this will remain one of the World’s greatest natural wonders.

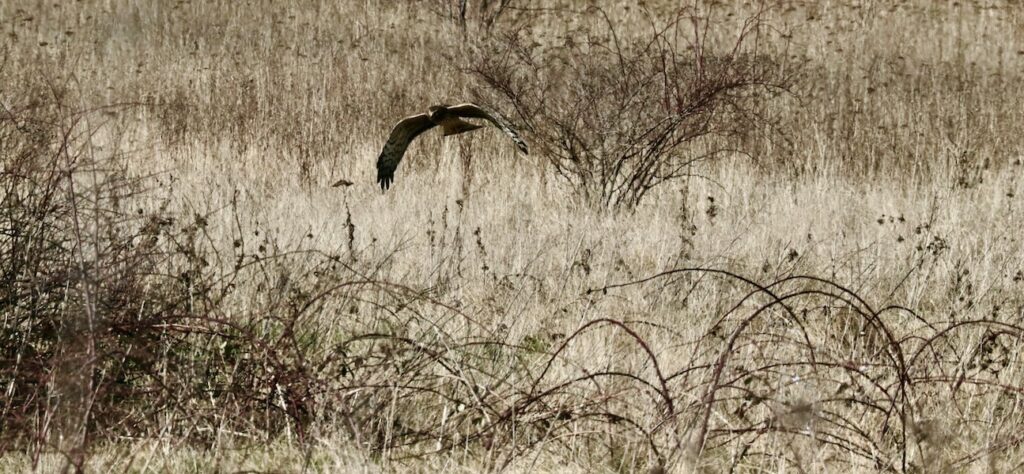

If migrating birds are to be successful they must find wild places along their flight paths where they can feed; and just as there are predators waiting for the wildebeest, there will be predators waiting for the birds as they come flying through. Few thing can hunt a bird more successfully than other bird, and during winter, the coastlines of the Pacific Northwest are ideal places to observe these avian hunters as raptors gather in numbers to seize the day. Not all will be feeding on birds flying through, some are looking for rodents living in grassland habitats along the route; and to be able to observe so many birds of prey is quite something, and the opportunity to photograph them is a bonus.

When photographing raptors, the usual problem is having an appropriate telephoto-lens to achieve the best results. Few of us can afford to buy the really long lenses — the ones where you need to train in a gym for months just to carry them; and then of course there’s the mortgage that has to be take out to buy one. My longest lens is 400mm and it’s a good one; with a converter I can extend its range to 800mm, but unless conditions are optimal and there is plenty of light, my pictures will be reduced in quality… When you can afford the longest and most expensive lenses what you are really doing is getting closer, is buying extra light.

For those who are doing things on the cheap, unable to afford those very long lenses with wider of apertures, it is necessary to think more creatively. Good pictures of birds are still possible, but the less well equipped find themselves out on only the sunniest days, because when you start shooting in lousy light with an inferior lens, your success rate will drop like a stone.

A Different Approach.

Apart from shelling out big bucks, perhaps there’s another way to deal with the situation. It is now almost impossible to get a better close up of a bird of prey — they are already out there somewhere; and the most impressive close ups are not always achieved with wild birds… not that it matters — better a tight shot of a captive bird than a disturbance in the wild because some idiot wants to get unreasonably close.

If you have an average to good camera — say an SLR with interchangeable lenses, and can afford one of the shorter telephoto lenses, something between 200 to 400mm, it is possible to take very good pictures of wild birds, providing the photographer is prepared to accept a wider frame than might initially have been hoped for. With the right background and appropriate exposure and framing, it is possible to achieve interesting results, although these might have more in common with landscape than wildlife photography — if we find it necessary to pigeonhole our endeavours. Whatever the label, the addition of a bird somewhere in the frame can raise an image beyond the expectations of a straight forward landscape picture.

I won’t suggest that a wide of a bird in the landscape is the same as a good close up; they are very different approaches to the same subject; but from a photographic perspective it is sometimes more interesting to see a bird in a natural environment, than a portrait of the creature in all its feathery detail. The important thing is to do the best that we can with the equipment we’ve got, rather than bleat on about all the things we don’t have and can’t do. When I started working as a wildlife film-maker I did so as a macro-photographer because I couldn’t afford the longer lenses, specialising in close-up photography; but when I could afford the longer lenses, it was possible to cover both disciplines. If you find yourself in a box, it’s good to climb out of it, but carrying the extra gear when you do so, is not quite so wonderful.

When I lived in Southern England I would travel from my home on the edge of town into the surrounding countryside to film wildlife. One day while driving to a friend’s house, I saw a barn owl flying low along a hedge line just before sunset, and noted there was enough light for an exposure. I returned the next day, and set up close by the field. The owl made a similar fly past to the previous day, but it did so a little later — this is common to many wild animals that set their internal alarm clocks to times dependent upon where the sun is in the sky. We no longer make such precise measurement in relation to the sun because we have lost contact with nature, but wild birds have not.

But I’m getting ahead of my story, back in the U.K. my ‘just before sunset barn owl’ allowed me only one shot per evening over the course of a week. The owl did its pass and was gone, and just after that, so was the light. Building an atmospheric evening sequence with two shots of an owl using a wide and a closer shot turned into many hours work, because I was attempting to film a barn owl in Britain when numbers were at their lowest ebb.

Living where I do now, I see owls more regularly, and often during daylight hours, which provides a greater opportunity to gain a variety of shots, as each is no longer that once in a blue moon event I had become used to. The point of the story is that being in the right place at the right time is 90% of the battle; and it makes sense to photograph events when they are both close to home and regularly available. Photography is a bit like life — the more chances you get, the easier things become.

Dingle.

When I was filming wildlife for television. I often used to shoot with something hanging in the foreground — the natural world has clarity, but how we see the natural world is not so clear at all. I would find an interesting piece of vegetation and hang it between the lens and the subject. Ironically, this artifice often makes things more real in our heads.

This intrusion into the frame is known as a ‘dingle’. But more recently, with the event of high definition digital images, the fashion for super-sharp images has caused ‘dingles’ which provide more impressionistic results, to fall out of favour… but not in my world. If the ‘dingle’ is several red berries and they are positioned very close to the camera, they will appear as out of focus orbs in the foreground and with a predator in mind, this adds something to the image. For this picture I waited for the owl to fly behind vegetation that looked colourful enough, and hoped that at some stage the actual event would occur. The risk was that the owl would continue hunting in full view, but never fly into the position required to make the shot; and I’d lost the opportunity to cover a range of other images because I was entirely committed to one event. This is one of the reasons why professional photographers often use captive predatory birds, although it takes a very special arrangement for such a bird to be flown without jesses — if there is a sudden urge to return to the wild, the bird might be lost.

A short-eared owl provides a free advert for The Nature Trust; this owl sits next to the path, and there are at least 10 other photographers with their cameras trained on the bird which doesn’t appear in any way disturbed. You could take this shot quite easily on a point and shoot camera or a mobile phone, but it is clear from the lenses being used around me that some are taking advantage of the close proximity of the bird for a head and shoulders close-up; but I think that is rather too obvious, but then, one might equally say… so is my picture.

No Worries!

I like to to playing with framing, and never worry about such things as the golden ratio; there is more nonsense talked about the correct balance of a picture than almost anything else in photography. Sometimes it’s good to feel uncomfortable. Out of kilter is interesting, and sometimes makes for a more dynamic picture. Framing in any case is a matter of opinion. One of the few good things about a short telephoto lens is that the birds being photographed don’t fill the frame unless they fly very close; this has the advantage of giving enough leeway to edit the framing later; and a lot can be done if your camera has plenty of pixels to play with, although pixels are not the answer to everything: the way sensors in the camera collect information and quite a lot else also comes into play.

How we see is also consequential. This century we have come to accept high definition images as standard, but because of the way our minds operate, motion blur seems very natural to us especially when we watch a movie, and if it isn’t there, things don’t feel quite right. This also carries across to still images, when something is moving quickly. Blur is still a major component of ‘looking natural’, with faces, particularly the eyes the preferential point of focus. No wonder we love owls… the birds are so flat-faced it makes focusing easy; but if the bird are in flight it’s nice to have the wingtips in motion, and achieving both at the same time can be a very fine balance.

Maybe our appreciation of sharper images will increase as the high definition capabilities of modern cameras becomes so good that ‘frozen in time’ is the norm. The irony is that to put our images up on the internet we have to downgrade the quality so that up-loading times are reasonable… and also because good H.D. images are likely to be stolen! Then we view the results on tiny phone screens… and just get the gist of what’s in the picture; even computer screens have limited definition. You have to question the logic — we are encouraged to spend small fortunes on regular upgrades to keep pace with technologies that move faster than a peregrine falcon can fall out of the sky, but in the end, don’t gain very much.

Framing a picture is down to personal choice.

If the sky is interesting, why not incorporate more of it into the picture.

My fear is that with the rapidly increasing development of natural environments, and the additional problem of climate change, ‘Pacific Skyway’ migration routes might become disrupted. Taking pictures of the birds is a great way to record what is happening along the way and how things change: every time somebody takes a picture and stores it, they inadvertently record events in a manner that, until recently, was impossible. Many cameras have GPS and each photographic event is dated, and this inadvertently provides data for the future.

For those who are not thinking

about how important recording natural events may prove to be in the future, there is always the simple pleasure of taking wildlife pictures just for the pleasure of it; and for those behaving responsibly there are still great opportunities. Wildlife pictures can be taken without disturbance, even without the most expensive, or the most powerful telephotos lenses.

There is a lot of one-upmanship with photography, partly because picture taking is so easy. Those who are good at it, often consider the process a special skill, but with cameras now doing so much of the work, it has become a fairly simple process that most of us can learn.

- There’s no point in being precious about it. Almost anybody is capable of taking an interesting picture of the natural world… *when they’ve learnt to stand in the right place!* And that’s encouraging. Rather than finding fault with images that don’t fit the repetitive formulaic approach commonly encouraged by photographic competitions, we should welcome different perspectives. Fresh ideas and new ways of doing things are to be encouraged; and if some people take pictures that do not win prizes, or fit in with the chocolate box school of photography, then maybe that’s no bad thing.

All the pictures of birds in this feature are wild — nothing is staged. No more than two hours was spent in one place at any one time; and apart from the wildebeest, all the pictures were taken during three visits to a single location totalling less than six hours of photography. There was no getting out of bed at the crack of dawn for better results… or any need to step off the path. I mention this only to indicate that ‘locations’ are the key to success, although some might say, ‘Get up earlier, spend more time, and you’d get better results’, but I’ve heard that before! A head of ‘The BBC Natural History Unit’ once told me that wildlife cameramen didn’t get up early enough for the best results. I laughed a lot — there weren’t that many of us doing it when I started — filming wildlife was an obsessive behaviour that teetered at the edge of mental illness, and I knew that most of us were getting up far too early; although almost certainly, I was the only one moaning about it.